São Paulo, Brazil – The fall of a tree deep in the heart of the Amazon rainforest has revealed a valuable secret that is now being carefully analyzed by a team of Brazilian researchers and archaeologists.

In October 2024, fishermen from the Arumanduba community, located in the Médio Solimões region deep within Brazil’s Amazonas state in the municipality of Fonte Boa, came upon a toppled tree and noticed that beneath it lay much more than soil, leaves, and branches.

They had uncovered what looked to be ancient funerary urns made of ceramic.

Intrigued by the material they had found, the fishermen reported the discovery to a local leader, who then informed the town’s Catholic priest. The priest reached out to the archaeology lab at the Mamirauá Institute for Sustainable Development, a research institute financed by the Ministry of Science.

Brazil Reports spoke in-depth with Márcio Amaral and Geórgea Layla Holanda, two archaeologists from the research institute who worked on the site’s excavation.

They detailed their painstaking work, the novel materials they uncovered, and shared insights into the discoveries they’ve made thus far after analyzing the artefacts for months.

Sophisticated ancient engineering

According to the archaeologists, a team of researchers from the Mamirauá Institute set out on January 3 from their headquarters in Tefé, Amazonas, en route to Arumanduba.

The journey took 24 hours by boat along the Amazon River.

Once they arrived, the team was welcomed by the local community. They set up camp about an hour’s walk from the location of the fallen tree, which it turned out had been concealing a fascinating archaeological site nestled underneath 40 centimeters (about 16 inches) of earth.

The site where the tree once stood is within the Médio Solimões region, which has been well known to the researchers since 2015.

This particular site was believed to be composed of artificial islands, dating back hundreds and possibly thousands of years, which formed a vast embankment – evidence that the researchers say points to the advanced construction and engineering capabilities of the region’s past inhabitants.

“So far we have identified 70 of these islands here in a very large site, but in this particular area we had not yet recorded this type of structure”, Amaral explained. He told these artificial structures were called “Aterrados e Cavadas” (loosely landfills and excavations) by local Indigenous peoples because of how the past populations changed the landscape.

“Indigenous populations of the past had a knowledge system that involved many aspects, including specific technologies for construction and agroforestry management,” said Amaral. “These were people who chose to live permanently in the floodplain, and they made it happen – they developed technologies and construction engineering to do so.”

The complexity of manipulating such rugged terrain wasn’t lost on the researchers.

“Everyone sees the pyramids of Egypt as the most beautiful and magnificent thing in the world, but the construction of these ‘Aterrados’ is just as impressive, if not more,” said Holanda. “They were living on these islands, managing the landscape, bringing plants closer to them, and modifying those plants. That requires immense knowledge.”

Funerary rituals

After one month of intensive field work, the team left the excavation site and brought the artefacts back to their laboratory in Tefé.

In total, the Mamirauá team uncovered seven funerary urns beneath the fallen tree. According to Holanda, the largest of the urns measures 90 centimeters (about 35 inches) across the opening and stands 55 centimeters (approximately 22 inches) tall.

With its interior filled with sediment, the vessel is estimated to weigh around 770 pounds. The smallest urn has a 60-centimeter (24-inch) opening, is 30 centimeters (12 inches) tall, and weighs approximately 400 pounds.

All of the urns will undergo restoration before further measurements can be conducted.

Preliminary analyses revealed that the funerary urns were made of ceramic, using a blend of clay and a non-plastic additive composed mainly of a freshwater sponge called cauxi, and caraipé – the ash from tree bark.

“Both materials are very commonly used in Amazonian ceramics because they contain a high amount of silica, which gives the ceramic greater lightness and resistance,” explained Amaral.

The archaeologist also pointed out the interesting shape of the vessels. “Typically, we find other types of shapes here. In these burials, there are open vessels, and many funerary urns have human-like forms. But these are huge vessels,” he told.

In addition to identifying the materials used to make the urns, the researchers confirmed that bones, likely human, were found inside them.

“The funerary urn is like a body designed to receive another body,” said Holanda.

According to the researcher, they believe an intricate process was undertaken to fit a body inside an urn. “A primary burial is performed where individuals are either buried in the ground or placed in baskets in the river so that fish consume the soft tissues. Afterward, the bones are disarticulated, cremated, go through a funerary ritual, and that body is then placed inside a new body – the urn – which is sealed and buried,” she said.

Lack of funding slows research

As the tedious analytical work progresses inside the lab, new pieces are often added to the puzzle.

For instance, while due to the red and white coloring over a white background, archeologists believe these urns belong to the Amazonian polychrome tradition of pre-Columbian ceramics found within the region, it’s still not possible to determine the exact age of the artefacts.

The team currently estimates that they could be anywhere from 200 to 3,000 years old. Narrowing this time range is one of their key challenges going forward.

Another important line of investigation is the possible relationship between the material under study and present-day Indigenous peoples who inhabit the region.

“This is an even greater step in the development of the research because we can’t yet correlate the findings with current Indigenous groups, as there are many peoples, and many were decimated in the Amazon,” Holanda lamented.

She added that this type of research is time-consuming and requires funding. “We don’t currently have the financial means to conduct these lab tests,” she acknowledged.

The Mamirauá Institute accepts donations, which go directly toward funding its projects and enabling important progress in research, such as its current study of the funerary urns.

According to the institute’s researchers, every contribution helps sustain this work, which plays a critical role in preserving important chapters of our collective history.

“Archaeology is a way to tell the stories that history books don’t,” said Holanda. “These are the silenced stories, the buried truths. It gives Indigenous peoples the protagonism they deserve – those who truly built the Amazon and who were already here in Brazil long before the invasion.”

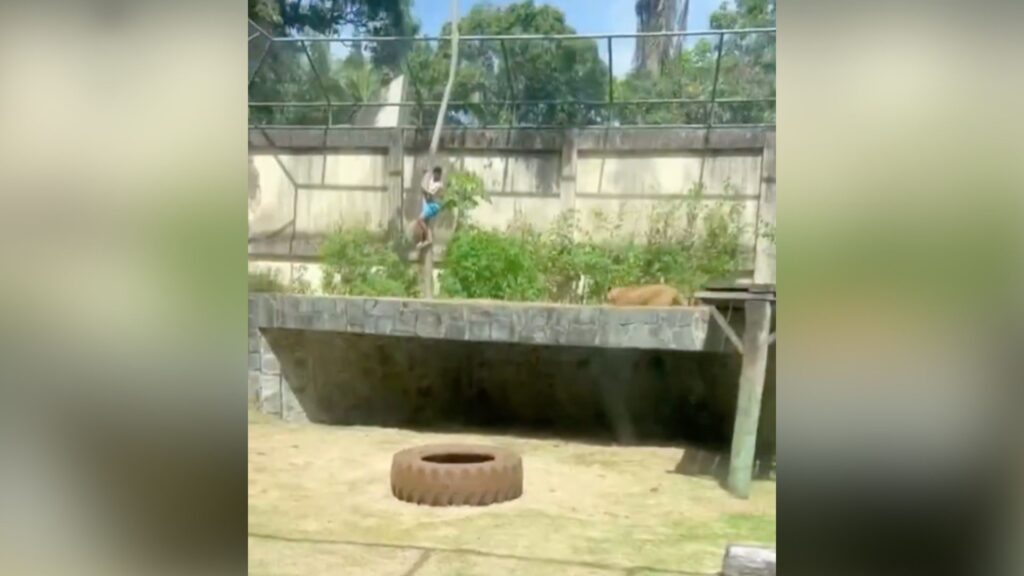

Featured image: Archaeologist Geórgea Holanda at the site where the funerary urns were found (photo credit: Geórgea Holanda/Mamirauá Institute)