São Paulo, Brazil – Diogo, a college student studying economics that was born and raised in Salvador, Bahia, the capital of Brazil’s fourth-largest state, said he used to always take the public bus to and from class.

Since June, Diogo — who asked that we not use his real name for fear of reprisal — said that he’s been too afraid to take the bus, as a wave of violence has gripped his state.

“I do an internship during the day, but the salary is low. I can’t commit all my income to taxis or [rideshare] apps, but I’m also afraid of risking my life on the bus,” Diogo told Brazil Reports. “Near my neighborhood, I’ve seen buses set on fire and people getting injured.”

“I didn’t go to class for a week in September,” Diogo said, adding that he’s never witnessed this level of violence in Salvador. “It’s a big city, there has always been violence, but not to this extent. We are afraid to leave the house.”

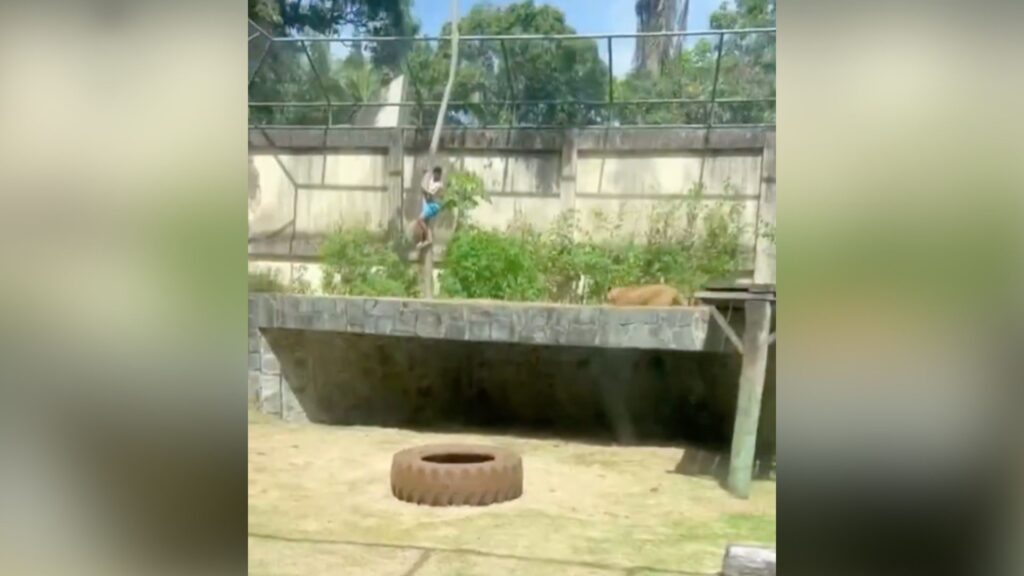

Escalating conflicts between local criminal gangs, as well as violence at the hands of police, are turning residents of Bahia into prisoners in their own homes.

Violent clashes between gangs and police are now commonplace. According to data from Bahia’s government, in September, 71 people were killed in clashes between criminals and police, including three police officers.

During the first week of October, at least 16 deaths were recorded. And in a single week between July 28 and August 4, 30 people were killed, as Bahia has become Brazil’s most violent state.

The most recent wave of violence began in June, following the alleged incursion of a drug gang from Rio de Janeiro, called Comando Vermelho, into Bahia in an effort to root out local criminal groups. However, the state has seen a steady increase in violent crime that some experts say mirrors Brazil’s rise in violence as a whole, particularly as it relates to violence at the hands of police.

According to the Brazilian Forum for Public Security, an NGO that gathers crime data in the country, Bahia had the highest number of violent deaths in Brazil last year, and is home to Brazil’s four most violent cities: Jequié, Santo Antônio de Jesus, Simões Filho and Camaçari.

The state also counted the highest number of killings by police, 1,464, or 22.7% of the total that occurred in Brazil, knocking off Rio de Janeiro from the top of the list for the first time since the study began being published in 2015.

At least five police officers have been reported murdered in Bahia since June, sparking a fierce retaliation campaign by police authorities.

“It is a crisis ordered decades ago, the result of successive and repeated mistakes made by the authorities,” Daniel Cerqueira, an analyst with the Brazilian Forum for Public Security, told Brazil Reports.

“Over the last 40 years, the homicide rate in Bahia has grown by 1,392% … In 1981, Bahia had 1,377 prisoners. Today, there are 16,169. The number grew by more than 1,000%,” he said.

According to Cerqueira, three factors have contributed to the rise in violence in Bahia, as well in other Brazilian states.

The first is a strong-arm approach to public security. Cerqueira argues that a more effective security policy could be reached with more cooperation between police and the communities they serve.

“You need to have mutual trust. When the police enter a community with a vision of war, an abyss is created, a feeling of reciprocal hatred and security policy becomes infeasible,” he said. “We have to regain control of the police, with the appreciation of police officers, but without letting this idea of force prevail.”

Second, Cerqueira argues that mass incarceration for drug convictions should be revisited.

“The war on drugs did not work and even created side effects for public safety,” he said. “The illicit drug market generates income for criminals, who invest in weapons, ‘soldiers’ and bribes.” In addition to not solving the security problem, according to Cerqueira, mass incarceration creates a breeding ground for organized crime, which have co-opted prisons across Brazil.

Lastly, Brazil is lacking a structured plan to address the root causes of the violence, according to the analyst.

“Brazil only deals with the symptoms, never with the causes,” Cerqueira argued. “It is necessary to invest in structural policies, based on evidence and not on ideological issues.”

Instead of only sending security forces into a community facing violence, Cerqueira said that authorities must also make investments in local education, culture and health.

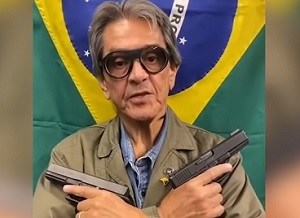

An ‘out of control police force’

In the United States and other countries, there is more civilian oversight of police forces. In Brazil, that task is taken up by the Public Prosecutor’s Office, which Cerqueira argued can’t handle the job.

“If the police kill a lot, this is not a specific or personal problem, but an institutional problem. We have an out-of-control police force and we need to rethink a new model of external police control,” he said.

In the short term, Cerqueira said that states should invest in police body cameras, as have been adopted in the US. “This can be very effective. Many studies have already shown a reduction in police violence after the cameras were installed,” he said.

Last week, Brazil’s government announced a new national public security plan, with measures to be adopted by 2026 to combat organized crime.

The government intends to make almost R$1 billion (USD $200 million) available for security operations, in addition to cooperation between institutions and strengthening intelligence activities, but did not include the measures mentioned by Cerqueira.