São Paulo, Brazil – Brazil’s government on March 23 launched a new anti-drug policy that aims to deal with the issue from a scientific and public health perspective. The idea is to format an approach free of prejudice, moving away from the repressive policies seen during the government of former President Jair Bolsonaro.

The latest study on drug use in Brazil, carried out in 2019, found that at least 3.2% of Brazilians used illegal substances in the 12 months prior to the survey, representing 4.9 million people. The figure is much higher among men: 5% against 1.5% of women. The most commonly consumed drug was marijuana, followed by cocaine.

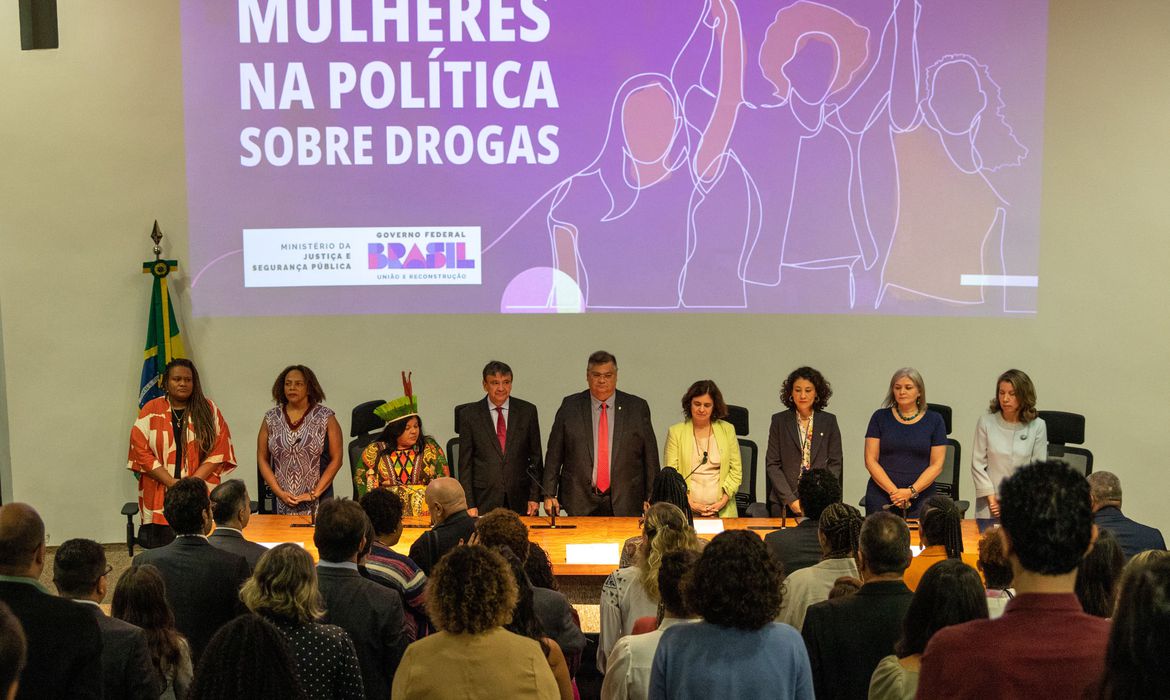

One of the main actions planned by the government involves the protection of women’s rights. Named the National Strategy for Access to Rights for Women in Drug Policy, the measure involves at least eight ministries, with the goal of promoting human rights and combating all forms of discrimination.

According to the National Secretary of Drug Policy Marta Machado, the program takes into account international commitments agreed to by Brazil, which point to the need for a careful look at the vulnerability of women who use drugs and/or live in a context of drug dealing.

Machado highlighted a United Nations report, which pointed out that, although the majority of drug users are not women, they are “disproportionately affected” by stigma and prejudice from society “and by many forms of violence, especially sexual violence.”

“That’s why, when we talk about these women, it’s a part of the population that is made vulnerable in different ways. In recent years, mainly due to the lack of coordinated actions, in addition to the lack of resources for health care networks and a policy of repression focused on violence, instead of intelligence and information,” she said.

According to the secretary, Black and Indigenous women are even more vulnerable, frequently living in the context of violent social struggles, including drug dealing in poor communities or in the Amazon region.

First actions

The new anti-drug program has taken its first steps with the formation of a working group consisting of eight ministries. This group will function as a permanent network to coordinate actions involving the citizenry and ensure women’s rights.

Also, Machado said that there will be financial support for NGOs that work with different groups of women, with the aim of guaranteeing, for example, access to work and income. Initially, the program will choose four NGOs per region (north, northeast, midwest, southeast and south), with funding ranging from R$ 100,000 to R$ 300,000 (USD $20,000 to $60,000).

In August, a second phase will be launched, with funding from three more organizations per region, totaling R$6 million (USD $1.2 million) by the end of the year.

“A new drug policy can only be built with social participation and in partnership with those at the forefront, working with different groups of women in their different complexities and needs,” said the secretary.

Looking at the marginalized

Minister of Justice and Public Security Flávio Dino said that it is necessary to “look at the marginalized” when dealing with the issue of drugs. According to him, drug addiction is a kind of slavery, which needs to be fought by the government. The minister also made it clear that the new policy does not mean weakening their stance on organized crime.

“Where some want darkness, fear, hatred, we want the light that democracy brings, and the union of ideas, projects and debates that a working group can provide. It is necessary to look at the excluded. It takes courage to address issues and humility to listen,” he said.

According to Wellington Dias, the Minister of Development, Social Assistance, Family and Fight Against Hunger, it is also necessary to develop scientific knowledge on the approach to this matter.

“The first step is to propose the creation of a scientific committee so that Brazil has a protocol and a way to deal with drug policy in the most different areas,” he said.

Dias also highlighted the need to improve the Brazilian justice system.

“How many times are there people who come to a criminal hearing, and instead of going to addiction treatment, they are sent to prison? It takes a scientific understanding that treats the user as a user, not just a criminal,” he said.