Despite being 53% of eligible voters, participation of women in Brazilian politics is still much lower compared to men. A law created in the 1990s aimed to increase the number of female candidates per election, but the law has been abused by politicians to syphon resources and register ghost candidates.

Originally passed in 1995 and updated in 1997, the law demands that all political parties must have 30% female representation among their candidates and must allocate at least 30% of electoral funds towards women candidates. (In Brazil, political parties are publicly funded, and distribution of public funds is related to each party’s parliamentary representation).

What we’ve witnessed in the last two elections has been a high number of ghost candidates — women who were registered as candidates by political parties only to fulfill the gender quota but don’t actually run for election.

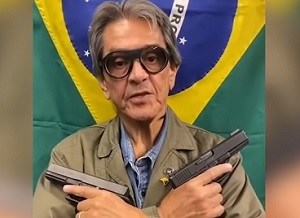

The biggest scandal happened in 2019 and led to the resignation of the then Minister of Tourism, Marcelo Álvaro Antônio. The minister was accused of organizing a scheme of four ghost women candidates in his state, Minas Gerais. The investigation showed that the resources went to companies linked to Mr. Antônio, while the candidates did not even campaign and received very few votes.

In addition to the fraud in Minas Gerais, the Electoral Court also identified ghost candidates in other states, such as São Paulo, Paraná and Alagoas. The president of the Superior Electoral Court, Judge Alexandre de Moraes, has promised strict control over the use of public money for women’s campaigns.

But the press has already reported suspected ghost candidates in the 2022 elections which take place on October 2. Newspaper O Estado de São Paulo identified at least BRL 5.8 million (more than US$ 1 million) in potential funding for ghost candidates.

The modus operandi is always the same: campaigns that receive large amounts of money, but post candidates that don’t campaign. Some of them have even participated in past elections, and received almost no votes at all.

The online news outlet UOL also conducted a survey that indicates the existence of at least 50 ghost candidates this year.

Why is female participation in politics still so unequal?

Women occupy only 15% of the seats in the Chamber of Deputies, where there are 513 parliamentarians, and 14% in the Senate, which has 81 members. In relation to black women, the numbers are even lower: despite being 28% of the Brazilian population, they do not occupy even 5% of the seats in Parliament.

Brazil occupies the 145th position in the ranking of the Inter-Parliamentary Union that analyzes the participation of women in politics in 192 countries. The country is behind almost all of Latin America. Until the Taliban regained power, even Afghanistan’s Parliament was composed of 27% women — a level of participation never reached in Brazil.

For the regional coordinator of the National Forum of Instances of Women of Political Parties, Juliet Matos, a reserve of chairs and resources for female candidates were important achievements. But she said that it is “essential to have more women in spaces of power within the parties, so that these achievements are made effective.”

Senator Leila Barros, the Women’s Attorney in the Senate, also defended more affirmative action to promote greater participation of women in politics, as well as to combat the historical distortions that have placed women in the background in Brazilian politics.

“Women have a broader view of society and are more inclined to dialogue, in addition to having greater knowledge of women’s issues such as abortion, health, harassment, motherhood and gender equality. On the other hand, we have already demonstrated that we have similar qualifications to men in any position,” said Ms. Barros.

A record number of candidacies, but will Brazil see an impact in votes?

The 2022 election had a record number of women candidates: 33% of the 28,000 campaigns registered in the Electoral Court are female. But these numbers may not reflect at the voting machines this Sunday. In addition to the suspicions of ghost candidates, nine of the 32 Brazilian parties have not yet transferred the minimum amount of 30% of the electoral funds for their female candidates.

“The lack of support is very complicated in the women’s campaign. Parties love to put women in photos, but when it comes to sharing the money, they end up favoring men,” said political scientist Débora Thomé to the UOL. “In the election, more resources are essential to have a better chance of winning.”

For the coordinator of the Women’s Bench of the Chamber of Deputies, deputy Celina Leão, women are still under-represented in Congress. The solution to this, according to her, involves a reflection on what everybody is doing every day to achieve more equality in politics.

“What I hear every day from many sexist and patriarchal men is that women don’t vote for women,” she said. “It’s with this challenge that we have to go to the polls. Women do vote for women. We need women to actually run as candidates, not to be ghost candidates and to be definitely supported by the parties.”