During his term, outgoing President Jair Bolsonaro created a scheme to buy support from Brazil’s congress which became known as the “secret budget.”

The shadowy system reportedly allocated $45 billion reais (USD $9 billion) to deputies and senators from his base with very little oversight between 2019 and 2021.

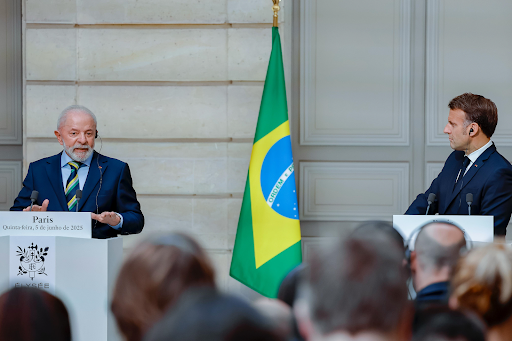

Incoming President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who was also president from 2003 to 2011, had his own controversial vote buying scheme, “Mensalão,” during his first mandate.

But under Bolsonaro, the secret budget has ballooned to about one-fifth of the entire discretionary spending budget, and its influence has swelled.

As Lula prepares to take office on January 1, there’s doubt about how his administration will manage the budget’s future, which reportedly already has $19 billion reais (USD $3.8 billion) set aside for 2023.

What is Brazil’s secret budget?

In 2019, the Bolsonaro administration allocated part of the national budget into a slush fund which is used to deliver money to deputies and senators and the cities they represent.

The fund is overseen by a “rapporteur,” most recently President of the Chamber of Deputies Arthur Lira, who is a Bolsonaro supporter, and the funds are delivered to legislators via so-called rapporteur’s amendments.

In normal practice, requests for funds from the national budget from legislators are constitutional and usually are allocated to projects involving local health, development and education initiatives.

But with the creation of the special rapporteur, the process of allocating the funds has become murky, and names of parliamentarians who benefit from public funds are often withheld.

In the past three years, Bolsonaro supporters in congress have been sending more resources to their cities and states in relation to opposition legislators, in what critics say is evidence of vote buying. According to The Guardian, 198 of the 225 deputies that received secret budget money were from far-right or center-right parties aligned with Bolsonaro.

“Whoever wants to help their city has nothing to hide, but whoever wants to do something wrong finds a way to hide there,” said deputy Aliel Machado of the secret budget.

Bolsonaro denies having created the secret budget, citing that he vetoed the project in 2019. However, he reversed his own veto and ended up approving the proposal shortly thereafter.

Corruption allegations tied to the secret budget

On October 14, federal police arrested two businessmen from the healthcare sector accused of inputting false information into the Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS), Brazil’s public health system, to divert at least $69 million reais (USD $13.8 million) in public funds. The source of the money was reportedly the secret budget.

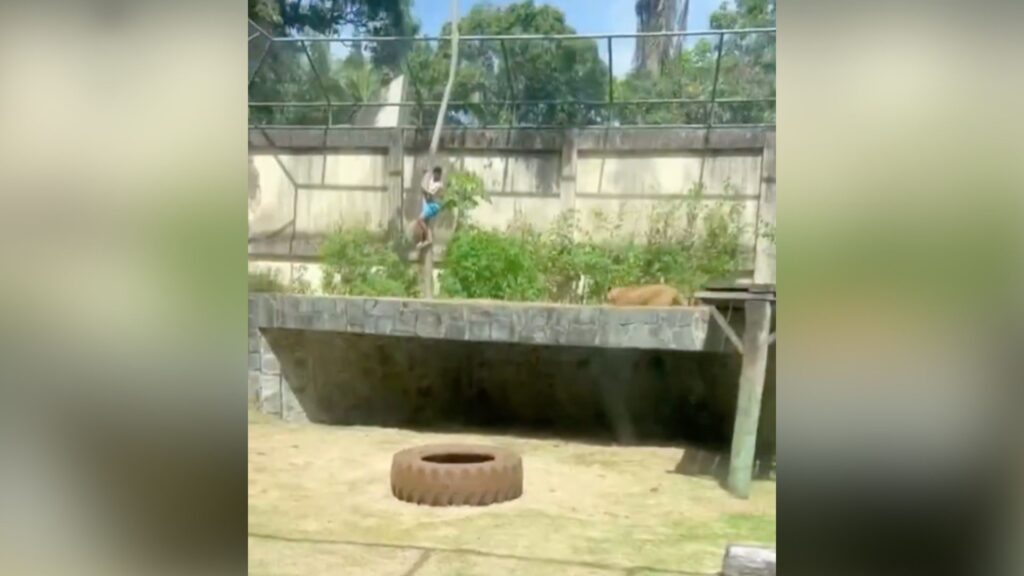

The operation in the state of Maranhão, in northeastern Brazil, was the first resulting from the scheme. Police found that a small town of 11,000 residents in the state registered 361,000 medical consultations and 12,700 finger X-rays in 2020 — a number which would amount to every resident of the city potentially breaking more than one finger in a single year.

According to investigations, the scammers inflated the number of X-rays and consultations in order to divert money from the secret budget to unknown destinations. Because of the lack of transparency, it is not yet known which deputy or senator asked for the money to be sent to that small town.

In another instance, Lira, the rapporteur and president of congress, approved a $26 million reais (USD $4.9 million) budget for robotics equipment for a school in his home state.

The school reportedly has no running water or electricity, and the equipment was provided by a company related to an acquaintance of Lira, according to former Environment Minister Marina Silva.

What will happen to the secret budget under Lula’s government?

During his campaign, president-elect Lula criticized the secret budget and indicated that he would like to end the scheme. Lula has called the secret budget a way of “extorting mayors and the population” and said that it “represents Bolsonaro’s submission to congress.”

But, in reality, putting an end to the rapporteur’s amendments will not be so simple. The scheme was created by the Bolsonaro government alongside Lira, one of the most powerful politicians in the country.

From a traditional family in politics, Lira has the support of the majority of the Chamber of Deputies to seek re-election in early 2023. Lula’s own party, the Workers’ Party (PT), announced its support for Lira’s candidacy, as it knows he doesn’t have a strong opponent to face him.

Lira is the secret budget’s biggest cheerleader, and he denies that there are any irregularities in the scheme.

Lula’s party’s outward support for Lira could be an indication that his administration will not end the secret budget — at least not in 2023.

The PT has said they intend to provide more transparency in the allotment of public funds, but have not announced a plan to carry this out.

Another reason to doubt that any action will be taken against the secret budget is that during his previous administration, President Lula had a similarly scandalous system he used to shore up support in congress.

In 2005, during Lula’s first administration, then-Deputy Roberto Jefferson revealed a kind of “allowance” to congressmen from seven parties in exchange for votes in favor of federal government projects.

The scheme became known as “Mensalão” and resulted in the arrest of many politicians and businessmen. More than 40 people were convicted for their involvement in the illegal payments, which amounted to $100 million reais (USD $20 million).

Lula’s use of a similar strategy to that of Bolsonaro puts in doubt his true intentions to get rid of vote buying schemes in the country.

The Supreme Court option

Politically, Lula is stuck between a rock and a hard place when it comes to the secret budget.

It’s hard to see his government being successful if he puts an end to the scheme that benefits so many congressmen, and ending the budget could earn him enemies in the legislature.

There is one option, however, that could both end the budget and keep Lula’s hands clean politically.

Brazil’s Supreme Court recently announced it would judge whether the secret budget is unconstitutional or not. If the court decides the payments are illegal, congress will have to suspend the scheme permanently, and Lula will not be to blame.

The case to examine the constitutionality of the secret budget is set to begin on Wednesday, December 7.