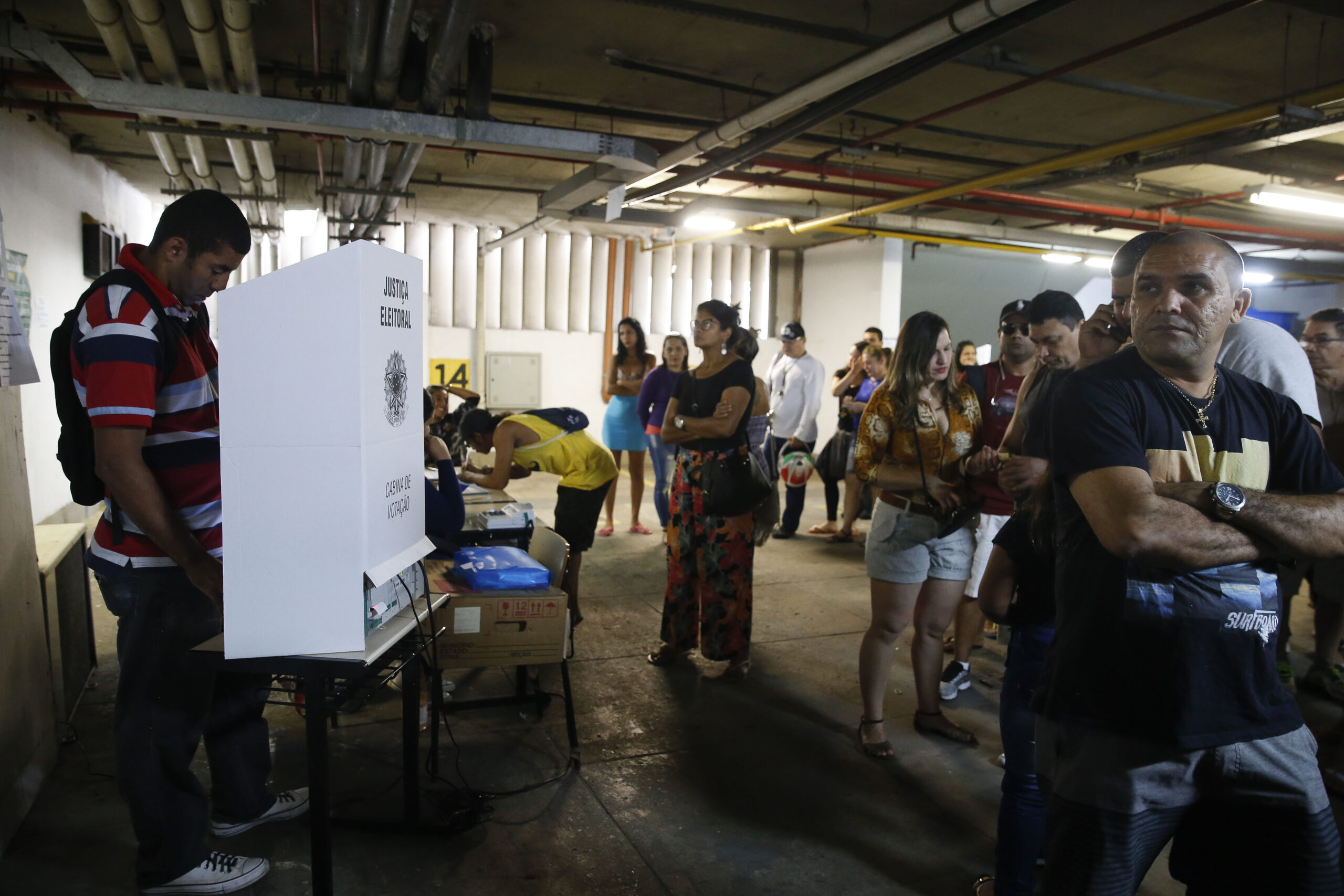

Brazilians will head to the polls on Sunday to choose a leader in what is shaping up to be one of the most consequential elections in decades.

Current President Jair Bolsanaro, a far-right firebrand, has sowed doubt amid his base about the election’s validity as he trails in the polls. His opponent, former leftist President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, has maintained momentum in the polls and courted his political opposition to his corner in the race against Bolsonaro.

Current polls suggest that no candidate will win outright in the first round of elections, and a run-off election between the current and former head of state is likely. However, taking into account the margin of error for these polls, which vary from two to three percentage points, a slight chance does remain that Lula could win in the first round. (In order to avoid a run-off election, one candidate must receive more than 50% of the vote).

Lula’s advantage over Bolsonaro is considerable. According to the research institutes, Lula fluctuates between 47% and 48% of voter preference, while Bolsonaro maintains his rates between 31% and 33%.

Old enemies, new allies

This week Lula’s campaign was endorsed by different sectors of society. The former president has received support from artists, intellectuals, businessmen, bankers and even his former political opposition — an uncommon occurrence between Brazilian politicians who don’t share similar ideologies.

Lula’s broad political front, known as Brasil da Esperança (Brazil of Hope), was formed with the help of his vice presidential candidate and former political rival Geraldo Alckmin. (Alckmin lost a presidential election to Lula in 2006).

Alckmin, a former member of the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB), was considered the main opponent of the Workers’ Party (PT) — to which Lula belongs — in recent decades. He has extensive experience in public office, holding important positions, including the governorship of the state of São Paulo. In all, he spent 16 years in charge of the wealthiest state in the country.

The curious thing about this alliance is that Alckmin and Lula have always had different points of view on how to govern. While Lula has been a champion of Brazil’s poorest, Alckmin is comfortable with the more affluent strata of society. Alckmin is recognized as a skilled politician, intelligent, very polite and able to move between the aisle.

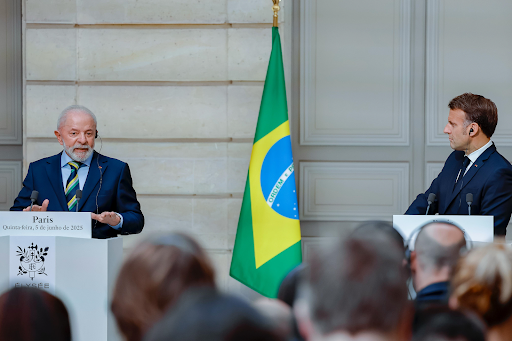

A damaged image abroad

The vice presidential candidate has been a key figure in drumming up support for Lula.

Last Tuesday, Alckmin helped organize a meeting of former ministers from the administration of President Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1995 – 2003). At the meeting, everyone, without exception, used the floor to express their desire for Lula to defeat Bolsonaro to rebuild Brazil and repair the country’s image within the international community.

A similar sentiment was expressed during a dinner of Brazilian captains of business on Wednesday night.

The event brought together around 40 business executives who control giant companies in the country. Among the guests were Luis Henrique Guimarães, CEO of Cosan, with business in the energy and logistics space; André Esteves, senior partner at BTG Pactual bank, Fábio Ermírio de Moraes, chairman of the board of directors of Votorantim, an investment holding company operating in areas such as energy, infrastructure, financial markets, construction materials, and mining; Luiz Carlos Trabuco, chairman of the board of directors of Bradesco bank and Benjamin Steinbruch, CEO of CSN, one of the largest steel companies in Brazil.

At the meeting, Lula asked that the group’s priorities be presented and heard requests to accelerate a profound reform in the country’s tax collection system, in addition to the adoption of strategies that transform Brazil’s economy into a green superpower, with sustainable growth practices that have a low impact on the environment.

According to participants at the meeting, Lula broke down resistance and seduced the group.

Brazil’s elite in attendance also reportedly expressed fatigue with the empty polemics of President Bolsonaro, which hinder the country’s business environment and development.

During his term, Bolsonaro has raised unsubstantiated claims about Brazil’s electoral system, has attacked the Supreme Court, promoted the devastation of the Amazon rainforest, and attempted to discredit vaccination policy during the high-point of the COVID-19 pandemic — all of which have affected Brazil’s image abroad.

Empty promises no longer have the same effect

Trailing in the polls, Bolsonaro, on the other hand, seems unable to get his ultra-conservative agenda to resonate outside of his loyal political base.

He has consistently campaigned on his now well-known conservative agenda, which includes extolling abstract values such as family, religion and patriotism, banning abortion under any circumstance, and expanding gun ownership.

By failing to present proposals to solve real problems that Brazilians face daily, such as unemployment, rising violence, the precariousness of the public health and education systems, Bolsonaro is failing to show himself as a capable leader — potentially paving the way for a Lula victory.