São Paulo, Brazil – Photographs released last month by Brazil’s National Indigenous Foundation (Funai) underscore the importance of monitoring and safeguarding Indigenous territories with strategies that ensure the lasting security of these communities.

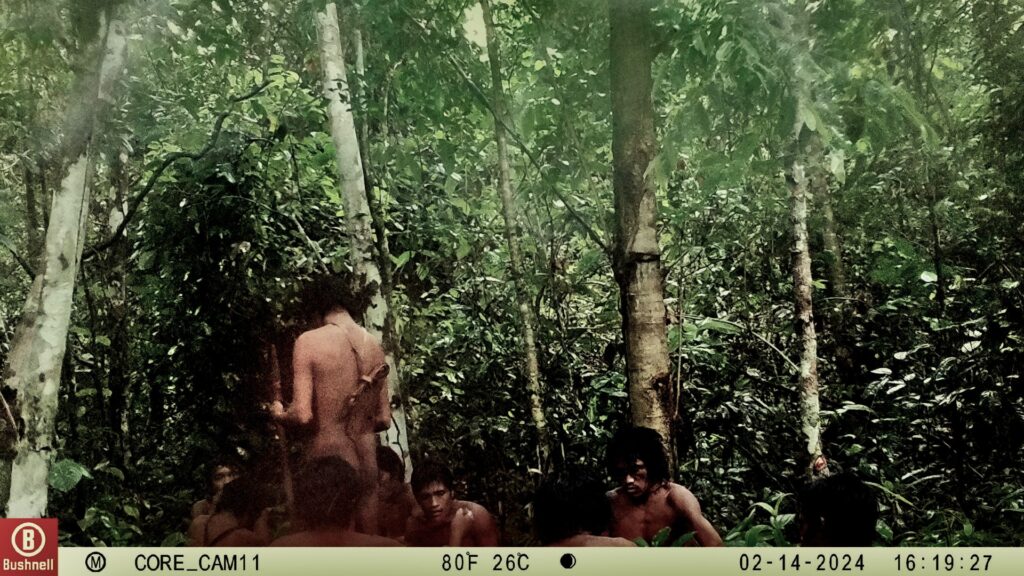

Funai documented images of isolated Indigenous groups in the Massaco Indigenous Territory, in the northwestern Rondônia state, and the Kawahiva do Rio Pardo Indigenous Territory, in the neighbouring Mato Grosso state. The photos were taken during monitoring expeditions conducted throughout 2024 by Funai teams.

This meticulous work is carried out by the Ethno-environmental Protection Fronts (FPEs), decentralized units of Funai specialized in tracking and observing isolated and recently contacted Indigenous peoples. FPE teams venture deep into the Amazon rainforest, supported by environmental and public security professionals who maintain permanent patrol structures in certain regions to better understand the habits and customs of these groups.

Massaco Indigenous Land

Located near Brazil’s border with Bolivia, the Massaco Indigenous Territory spans 421,895 hectares. Officially demarcated in 1998 during President Fernando Henrique Cardoso’s administration, it belongs to isolated Indigenous groups whose ethnic identities remain unknown. As a demarcated land, it benefits from ongoing government protection efforts, including inspections to curb illegal logging, resource extraction, and invasions by land grabbers. The territory also hosts a permanent base for the Massaco Ethno-environmental Protection Front.

Between January and April of last year, a Funai expedition monitored the living conditions of the isolated groups residing there. Led by veteran indigenist Altair Algayer—who has over 30 years of experience in the field—the mission gathered crucial insights.

(Image credit: CGIIRC/Funai)

In conversation with Brazil Reports, Algayer recounted that Funai first identified the group in 1988 and has since conducted regular expeditions to assess their health, way of life, and ensure their protection. According to him, the Brazilian government must provide the necessary resources for Funai to maintain its monitoring teams within and around the Indigenous territory to prevent invasions.

“Every year, Funai faces financial difficulties in maintaining personnel and structures within the Indigenous Territory to carry out surveillance work,” Algayer said.

His team was responsible for documenting signs of Indigenous activity in early 2024. Over five days, the expedition covered approximately 65 kilometers, uncovering traps set by the Indigenous inhabitants, temporary shelters, honey collection sites, and evidence of hunting activity.

In February, camera traps installed in the rainforest captured images of a group of Indigenous men collecting axes and machetes left for them by Funai officials. The photographs revealed nine men, estimated to be between 20 and 40 years old, all appearing in good health.

(Image credit: CGIIRC/Funai)

One concern raised by members of the expedition was the detection of Indigenous presence at the outermost edges of the demarcated protection zone. This may indicate that the group is expanding its territory in search of survival resources, potentially bringing them into contact with non-Indigenous communities—an encounter that could pose significant risks.

“Another worrisome factor is the possibility of unplanned contact with outsiders. This could happen if isolated groups seek out contact on their own, or if outsiders—such as illegal settlers, adventurers, or curiosity seekers—encroach upon their land. The consequences could be catastrophic,” Algayer warned.

With decades of experience tracking isolated peoples, Algayer detailed the techniques used to locate and follow their movements.

“We identify their presence through the traces they leave in the forest: trails, footprints, cut-down trees for honey collection, shelter constructions, fire pits, fruit gathering spots, and the raw materials they use to make artifacts and tools,” he explained.

According to Algayer, this type of research helps determine cultural practices, social organization, ethnic identity, demographic trends, and even population growth through evidence of the presence of children.

The Kawahiva do Rio Pardo Indigenous Territory

Unlike Massaco, the Kawahiva do Rio Pardo Indigenous Territory has yet to be officially demarcated by the Brazilian government, leaving its isolated inhabitants vulnerable.

The reserve spans 411,844 hectares in the state of Mato Grosso. As part of the demarcation process, its territorial boundaries have been formally declared by the Ministry of Justice following anthropological studies conducted by Funai. However, the process has been stalled for over two decades due to ongoing legal disputes by local ranchers who contest the land’s ownership.

Jair Candor, coordinator of the Madeirinha-Juruena Ethno-environmental Protection Front, led Funai’s 2024 expedition into the Kawahiva do Rio Pardo territory. With 36 years dedicated to protecting Indigenous peoples, Candor is one of Brazil’s most experienced sertanistas, or specialists in Brazil’s most isolated regions.

During the July 2024 mission, his team quickly confirmed the presence of Indigenous inhabitants. They discovered footprints—including those of children—along with honey collection sites and various handmade tools.

“Every expedition requires careful planning of routes and logistics for the region we’ll cover. Once in the field, we look for signs: trails, temporary camps, hunting and fishing spots, and fruit-gathering areas. When we find these traces, we can confirm their presence,” Candor told Brazil Reports.

The presence of children, he noted, is a positive indicator that the group is living in stable conditions, demonstrating population growth and the formation of new family units.

The frequency of these expeditions varies depending on the security situation in each territory. “If the area is calm, we conduct one or two expeditions per year. But if there are invasions, we increase the frequency—sometimes up to four times a year—to keep the territory protected,” Candor said.

At the conclusion of the 2024 mission, his team left tools such as machetes and axes at strategic locations within the reserve and installed new camera traps to gather more information on the group’s behavior. This data will help refine protection strategies for the territory.

The type of work Candor, Algayer and other protectors of Indigenous people in Brazil are doing is constantly threatened by political upheaval and budget cuts. During the administration of President Jair Bolsonaro, Funai’s team and budget were all but completely gutted, and U.S. President Donald Trump’s recent demolishing of USAID is impacting Amazon conservation efforts and Indigenous councils who received financial support from the development agency.

Candor issued a stark warning: “If Funai stops this work, these isolated groups will be wiped out.”

Featured Image: Photographic record of indigenous people in Massaco Land. Image credit: CGIIRC/Funai via Funai