São Paulo, Brazil – On the afternoon of September 28, two teams from the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio), an agency linked to Brazil’s Ministry of the Environment, were attacked in the southern part of Amazonas state, in the Aripuanã National Forest.

The institute’s agents were carrying out an inspection of illegal logging and despite being accompanied by members of the National Security Force — a special unit of military and civilian police — they were ambushed in the forest. A group of illegal loggers surrounded them and set fire to two ICMBio trucks.

ICMBio’s communications office, told Brazil Reports that the inspection carried out by ICMBio agents identified 550 cubic meters of illegal timber, as well as weapons, equipment and vehicles used for illegal deforestation.

The equipment was seized and four suspects were identified and fined R$7.6 million (USD $1.5 million). The organization also said that operations to combat illegal deforestation in the region will intensify and those responsible for the attack will be punished in accordance with the law.

Attacks like this are an unfortunate reminder that the Amazon is now the most dangerous place in the world to work as an environmentalist.

A report released last month by Global Witness, an environmental watchdog, revealed that one in five of the 177 environmentalist killings that happened in 2022 occurred in the Amazon. Colombia and Brazil, two countries with vast territory in the Amazon, topped the list for most environmentalists killed at 60 and 34 respectively.

“This frightening figure is the translation of the absence of the State: The absence of public policies focused on the protection of defenders, the preservation of traditional territories and the preservation of the environment,” Gabriella Bianchini, Senior Consultant and COP Project Lead at Global Witness, told Brazil Reports by email.

Bianchini said that environmentalists in the region are on the front line of the fight against predatory exploitation of the Amazon, which is one of the largest greenhouse gas storers on the planet and plays a crucial role in stabilizing regional temperatures.

The Amazon is also home to millions of species of animals, one third of all tropical tree species on the planet, and more than 40 million people, including over 500 Indigenous and ethnic groups.

Under the previous government of President Jair Bolsonaro, the administration severely cut resources for entities that protect the Amazon, and land grabbers, miners and loggers were all but invited into the Amazon on a red carpet.

Since taking office in January, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has sent security forces into Indigenous territories to help regain land taken by ranchers and miners, however, in many parts of the Amazon, lawlessness and a sense of impunity for those who harass and threaten environmentalists persists.

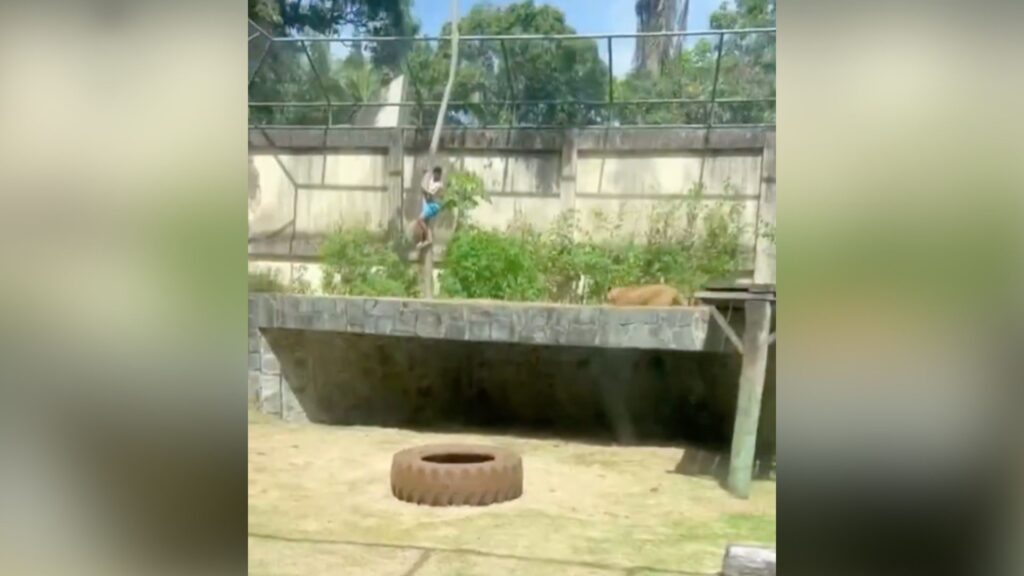

In May, Neidinha Suruí, leader of the Kanindé Ethno-Environmental Defense Association, and a group of journalists and Indigenous activists were denouncing illegal cattle farming and deforestation on the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau Indigenous land near Brazil’s border with Bolivia when they were intimidated by a group of ranchers.

“We were surrounded by 50 invaders of the Indigenous land,” Suruí told Brazil Reports. “We noticed that some of them were armed, with weapons under their clothes. They weren’t wielding their weapons, but we could see from the [bulges in their clothes] that some of them were armed.”

According to Suruí, the men identified themselves as representatives of local agricultural producers and claimed ownership of part of the Indigenous territory, which has been demarcated for Indigenous use since 1991.

Suruí said she was kept captive for four hours before she and a group of Indigenous people were released. The journalists and activists that also accompanied her were only allowed to leave after Suruí was forced to give an interview to a journalist sympathetic to the land grabbers.

“I left with the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau [people] and they kept the group of journalists and [an activist] locked up, who were released five hours later after I was forced to give the interview to whoever they wanted, saying whatever they wanted,” said Suruí.

Last year, the murders of British journalist Dom Phillips and Brazilian activist Bruno Pereira in the Amazon’s Javari Valley brought international attention to the dangers facing those who report abuses in the rainforest.

Over a year on, the danger persists.

“We still receive reports of violence, threats, torture, intimidation, attempts at criminalization and other non-lethal violations,” said Bianchini. “Defenders in the Amazon are still living a reality of extreme violence.”

According to the rights expert, countries in the Amazon must make meaningful changes in order to protect the rainforest and those who defend it. This involves tackling three main fronts:

- Create a safe environment for land defenders: Governments must protect the rights of defenders, including the universal right to free, prior and informed consent, the rights of indigenous peoples to their livelihoods and culture, the right to life, liberty and freedom of expression, and the right to a safe, healthy and sustainable environment.

- Leadership to denounce, investigate and seek accountability: Efforts to strengthen policies and enforcement should be combined with monitoring attacks against defenders, as well as what happens after attacks, to help combat impunity.

- Promote the legal accountability of companies: Require companies and financial institutions to carry out due diligence on human rights, environmental and climate risks in all their global operations. This would make companies more transparent and accountable for violence and other harms perpetrated against land and environmental defenders.

The traumatic experience that Suruí and members of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau Indigenous territory went through back in May, might have resulted in something positive.

According to the Indigenous leader, after they were temporarily sequestered, the Kanindé Ethno-Environmental Defense Association contacted the Brazilian government, which arranged for the National Security Force to be sent to reinforce protection in the indigenous territory.

Her concern, however, is that the troops will only stay until the end of December. She’s currently petitioning the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) to guarantee resources and investments so that security forces can stay in the region for longer.

“This protection needs to be constant. We need a guarantee that FUNAI will have the resources to maintain them.”