São Paulo, Brazil – A study made by Brazilian researchers and published on October 5 in the renowned scientific journal Science, one of the world’s most respected academic journals, has found solid evidence that a significant part of the Amazon region has been inhabited by traditional indigenous peoples for at least 12,000 years.

Over the course of five years of research, Vinícius Peripato and Luiz Aragão managed to identify the existence of 24 uncatalogued and completely unknown archaeological sites hidden beneath the forest.

Peripato, a geographer, holds a master’s degree in Remote Sensing from the National Institute for Space Research (INPE) and is about to complete his doctorate in the same field and institution. He is supervised by Professor Luiz Aragão, who holds a master’s and doctorate in Remote Sensing from INPE and co-authored the publication.

In order to understand every detail of this work, which tends to trigger profound reflections on some of the issues currently being debated in the country, such as the right of indigenous peoples to claim ownership of their traditional lands, Brazil Reports spoke to the two researchers.

Their research provides scientific evidence capable of dispelling the uncertainties and insinuations that often surround discussions on this sensitive subject.

Pre-Columbian Amazon

Peripato told Brazil Reports that he was already aware of the existence of archaeological sites in deforested areas of the Amazon, especially where cattle are raised, and decided to look for similar structures where the forest is still preserved. He said that the data was obtained using Lidar (Light Detection and Ranging) technology.

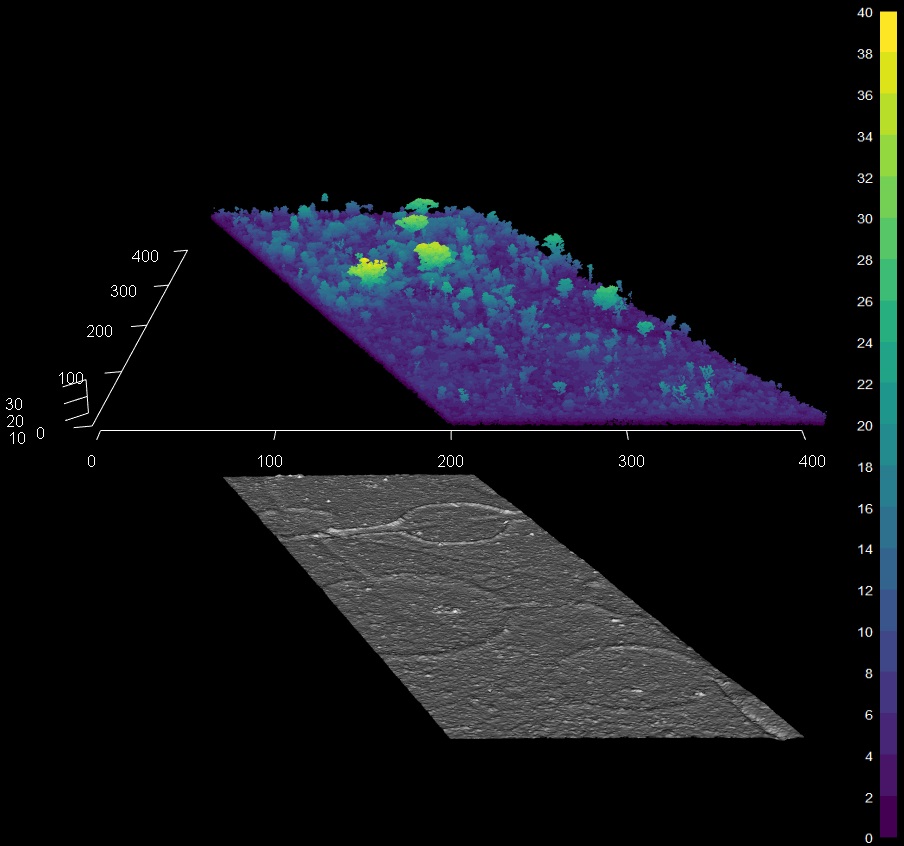

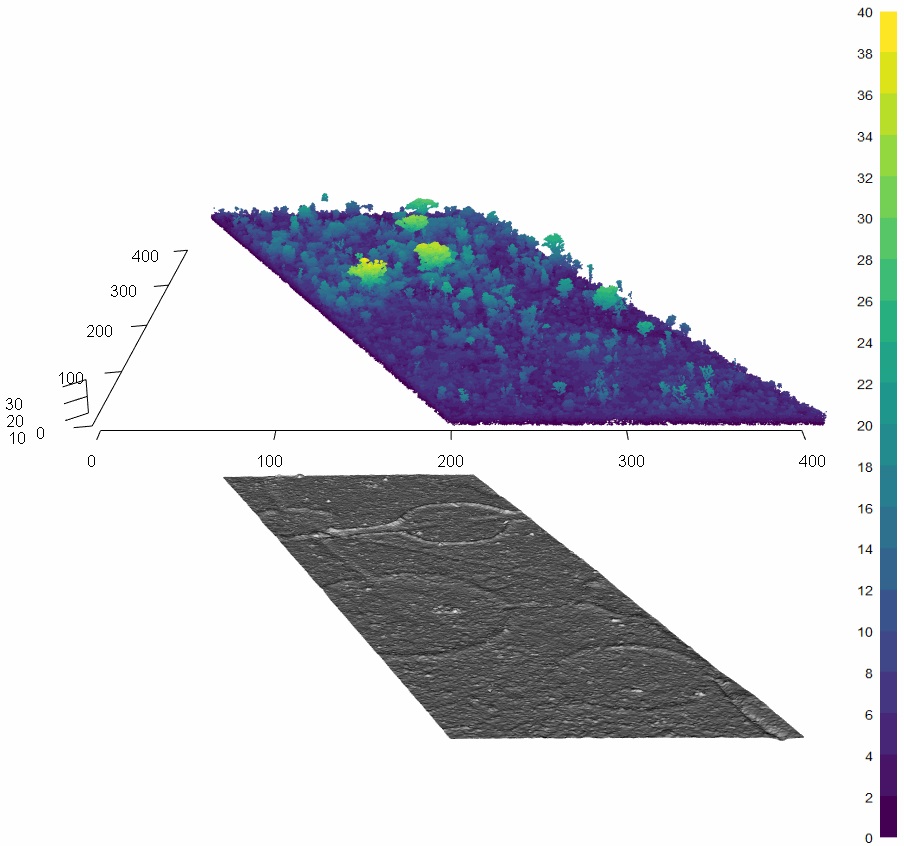

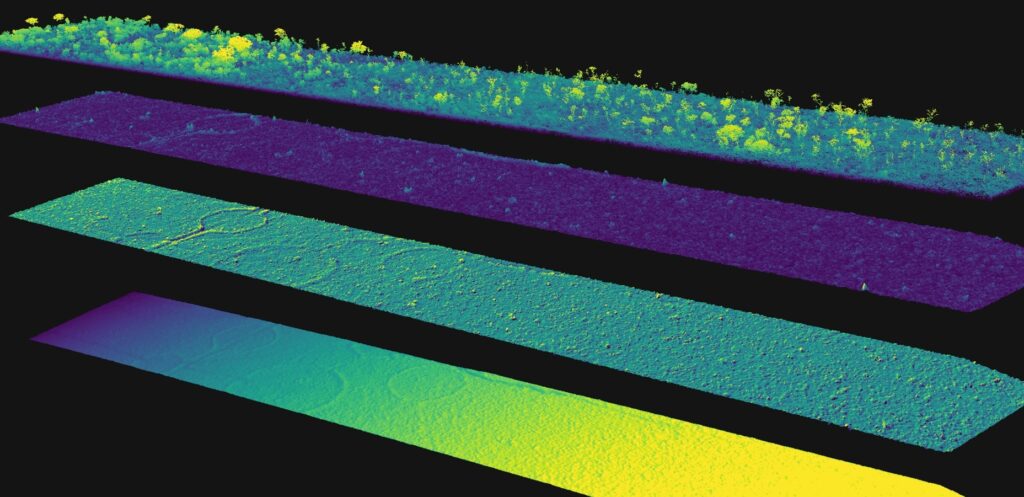

Lidar is a laser sensor that is installed on a drone or aircraft and records everything on the ground while these devices fly over the area. In Peripato’s words, the system works like an X-ray, exposing every detail that exists, even if it is covered by trees or dense vegetation.

“You can make a 3D reconstruction of the entire forest. Then you can do a digital removal of the forest. That’s what allowed us to look under the forest, in the relief, for these structures throughout the Amazon,” explains Peripato.

By analyzing the data that was randomly collected by the Lidar system over an area of more than six million square kilometers, Peripato and Professor Aragão discovered the existence of these 24 new archaeological sites.

But the researchers believe that the Amazonian soil still hides between 10,000 and 24,000 of these works. These are geometric shapes and figures built into the ground by moving earth, known as geoglyphs. As per Professor Aragão, on average, each of these structures is between 100 and 200 metres long and up to five metres deep and have been found throughout the Amazon.

“These structures are distributed throughout the Amazon. We have new structures that have been identified in the state of Amazonas, the state of Amapá, Pará, Mato Grosso, and Acre, so they are distributed throughout the Amazon,” says the professor.

For the experts, the structures alone are not enough to reveal more details about the way of life of the people who built them, but they are strong enough evidence to determine that the Amazon region has been inhabited by traditional peoples for centuries.

“It shows that the Amazon has always, since before its discovery, been a region occupied by these native peoples and we must take this into account,” says Professor Aragão.

The professor’s statement is a powerful argument at a crucial moment when some sectors of Brazilian society and politics are attempting to diminish the property rights of indigenous peoples.

The Temporal Limit Battle

On September 27, the Brazilian Senate approved the so-called Temporal Framework Law, according to which new indigenous territories can only be demarcated if it can be proven that the spaces were already occupied by them in 1988, when the country’s current Constitution came into force.

The problem with this thesis is that it disregards the fact that countless indigenous communities have relocated over time for various reasons, such as conflicts, persecution, climatic factors and diseases.

“Even before the Portuguese arrived, there was a dynamic in the Amazon, including indigenous conflicts between themselves. There are several sites that have been abandoned, some crops have fallen due to severe droughts and other climatic events,” explains Peripato.

On October 20, President Lula da Silva, however, vetoed the Temporary Framework Law, guaranteeing the indigenous people a momentary relief, as the presidential veto will be reviewed by the Congress, which may choose to reject the veto, leading to the enactment of the Law in the form in which it was approved by Parliament.

Eliésio Marubo, the legal attorney for the Union of Indigenous Peoples of the Javari Valley, is one of Brazil’s main indigenous leaders and has even been tipped to take over the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, created by the Lula government and headed by Sônia Guajajara.

Brazil Reports spoke to Dr. Marubo about the recent archaeological discoveries and their impact. For him, scientific research sheds light on the debate and recognizes something that indigenous peoples have never doubted.

“This only reinforces what we have been saying for a long time since this issue was debated in society, that our right is not limited to the Constitution of 1988. It’s what I call the right of full occupation, even more so in the Amazon,” said Marubo.

Dinamam Tuxá, coordinator of the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (Apib) and one of the leaders of the Tuxá people, who live in the west of the state of Bahia, also rejects the temporal framework thesis. Speaking to Brazil Reports, he incisively defended the right of indigenous peoples to be recognized as the true owners of the lands where they live.

“Even before the Brazilian state existed, the indigenous peoples were already here and they are entitled to their territories, and they have the right to their demarcated territory,” Tuxá told Brazil Reports.

In Tuxá leader’s opinion, the statement comes from a reasoning that seems obvious, yet it meets with resistance from sectors of the country, especially agribusiness. From his perspective, the temporal limit thesis is an attempt to reread the Constitution, which in no article establishes a deadline or limit for the demarcation of indigenous lands.

“They try to distort or create new interpretations of the constitutional text in the name of an interest. And who has this interest? The big corporations, agribusiness. For what purpose? To exploit in the name of capital and then, in this correlation of forces, including political ones, the indigenous peoples are the ones who suffer the most,” says Tuxá.

Demarcation and Protection

For Tuxá and Marubo, however, the issue of land demarcation is just the beginning of the Brazilian state’s ongoing efforts to protect indigenous communities. Eliésio Marubo points out, for example, that the Vale do Javari Indigenous Land has already been demarcated and homologated by Brazil since 2001, but he says that the current situation in the reserve is one of complete insecurity with the advance of invaders and criminals into the territory.

And it’s worth remembering that the Javari Valley was the scene where British journalist Dom Philips and Brazilian indigenous activist Bruno Pereira were brutally murdered in June 2022.

“With the spotlight shining on the Javari Valley, unfortunately we’ve had nothing, or almost nothing, back from what we had been discussing with the political world. Unfortunately, the state bureaucracy, the lack of care on the part of the federal government has meant that organized crime has won this battle in this first moment,” reflects Marubo.

The National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (FUNAI), says that Brazil has 761 indigenous lands, which corresponds to 13.75% of its territory. Of this total, 475 reserves have properly demarcated and regularized. Dinamam Tuxá, however, says that in many regions demarcation processes are stagnating, such as in the state of Bahia.

He said that there, the slowness and inertia of the state in recognizing the property rights of indigenous peoples has aggravated conflicts motivated by disputes over territories with the agricultural sector, in particular.

According to him, faced with the lack of action by the Brazilian government, the local indigenous people have started to carry out what he calls “self-demarcation of lands”, in other words, the indigenous people themselves establish and mark out the boundaries of their territory. Tuxá warns, however, that these actions could trigger a wave of violence.

“When a process of self-demarcation begins, there is also a process of criminalization and a lot of violence against indigenous peoples. The consequences of this are the deaths of many young people, leaders and threats. This has been happening systematically in the state of Bahia, especially in its extreme south.”

Tuxá also affirmed that the demarcation of lands represents the existence of indigenous peoples as the specific and differentiated beings that they are. He expressed his frustration about the temporal limit thesis, which in his words is nothing more than a legislative genocide and an attempt to erase indigenous peoples from history.

“They want to uproot indigenous peoples from their traditional territories in order to exterminate our existence from Brazilian territory once and for all.”

Brazil Reports reached out to the Brazilian government, through the ministries of the Environment and Indigenous Peoples, to comment on the complaints and demands presented in this report by the indigenous leaders, but unfortunately we received no response.