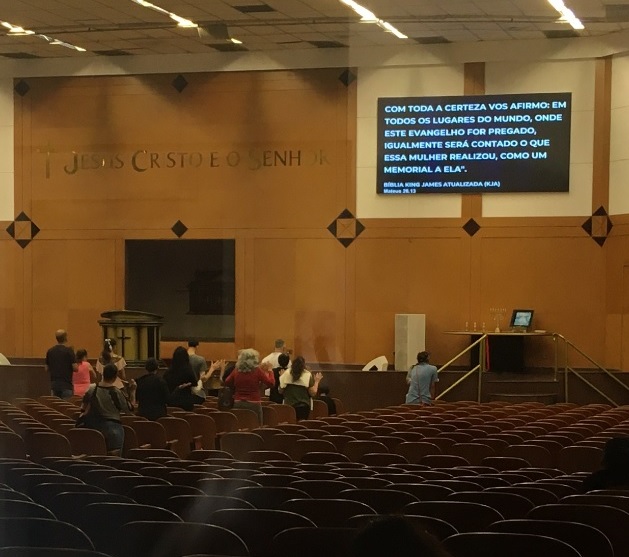

On a rainy Sunday night in the Mooca neighborhood of São Paulo, Brazil, the Vitória em Cristo Assembly of God evangelical church gathered for service. Around 300 people sat in the vast hall awaiting a sermon from Pastor Cristian Oliveira.

The pastor began the service with a welcome message and a string of prayers which were echoed by his faithful followers. In less than five minutes, however, the sermon’s focus shifted away from religious advice and dove right into politics — something not uncommon among evangelical pastors in Brazil today.

“Our church has very firm positions,we don’t stay on the fence. We believe in the exercise of citizenship,” shouted Pastor Cristian. He told his followers that Christians should always profess their faith and keep away from communist ideals, “because we are Christians!”

Another pastor, Giuliano Dias, took the stage next. He read a passage from the Book of Jeremiah in which God commands the captives who left Jerusalem to Babylon to build houses, marry, have children, and seek to maintain peace in the city.

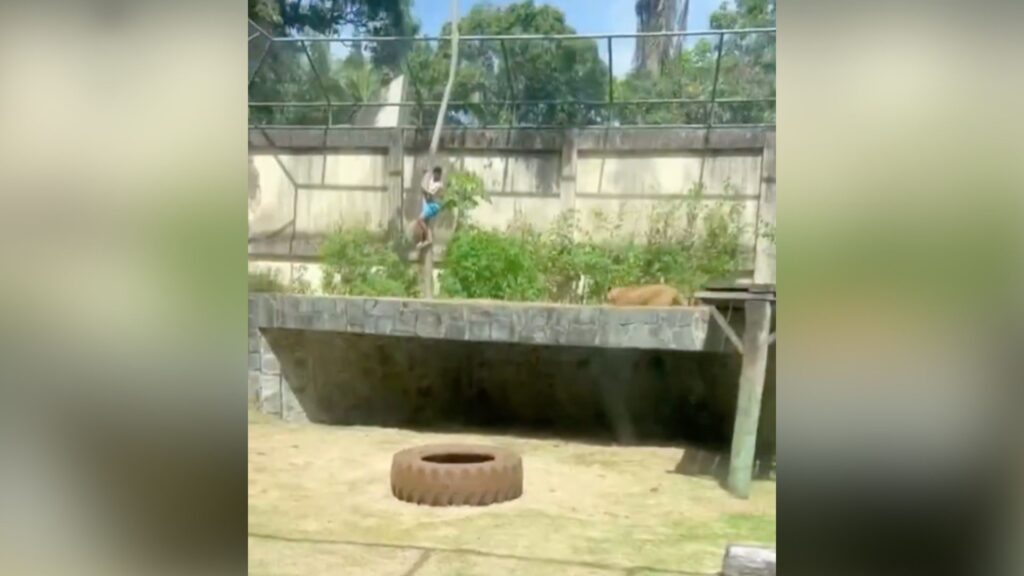

Vitória em Cristo Assembly of God Church, in São Paulo / Thiago Alves, Brazil Reports

In a mixture of bellowing screams and low whispers, Pastor Giuliano connected the passage about the hope of building a strong Christian society to modern-day Brazil. He emphatically said that today, Brazil is the country of hope and opportunities and told the audience that Brazilians no longer must leave the country to seek better living conditions.

Without providing context, the pastor pointed out that Brazil has a lower inflation rate than the United States for the first time in history, that the price of fuel in Brazil is lower than in Europe, and that in 2023 the Brazilian GDP growth will be higher than that of China.

“On the 30th of this month we will give an answer,” barked Pastor Giuliano, referring to the second round of presidential elections later this month between current President Jair Bolsonaro and former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. “The world will know a nation whose God is the Lord. In a short time we will be a first world nation.”

Evangelical sermons in Brazil were not always this politically charged. But over the past 37 years, the political force of Brazilian evangelicals has coincided with the growth of the community nation-wide, molding a new political landscape which could play an important role in the country’s upcoming elections.

The growth of the evangelical political base in Brazil

During Brazil’s military dictatorship from 1964 to 1985, the country’s evangelical community stayed out of politics for the most part, according to Paul Freston, the author of Evangelicals and Politics in Asia, Africa and Latin America.

After democracy was returned to Brazil in 1985, however, the community began a more dedicated foray into political participation. That year, the Assembly of God, the world’s largest Pentecostal denomination, announced they would endorse Brazilian candidates running for office, Freston told The Atlantic in 2018.

Since then, evangelicals’ political power has coincided with the growth of their communities across Brazil.

In 1980, those who identified as evangelicals in Brazil were just 6.6% of the population, compared to 22.2% in 2010, according to the most recent census data. In 2010 Catholics accounted for 64.6% of the population in Brazil. (Brazil’s 2020 census was postponed because of the COVID-19 pandemic and results from the latest census are expected back in December 2022).

However, a January 2020 Datafolha Institute survey on religious diversity in Brazil revealed that evangelicals now make up 31% of the country’s population, while Catholics account for 50%.

The strength of evangelicals is also reflected in the composition of Brazil’s Congress.

In the current legislature, 191 parliamentarians constitute the Evangelical Parliamentary Front, a political caucus championing their special interests. The commission is composed of nine senators and 182 deputies, which corresponds to 32% of the total number of Brazilian parliamentarians. The group’s agenda includes abortion prohibition and protection of traditional, conservative family values.

Political scientist Vinícius do Valle, a PhD from the University of São Paulo, spoke with Brazil Reports about politicians’ interest in courting the evangelical vote.

He considers evangelicals a heterogeneous, although diverse, political base that is easily mobilized by their religious leaders. According to Mr. do Valle, evangelicals tend to visit church often and develop a protection network capable of offering, in addition to religious support, new friends and social assistance such as job opportunities.

“Conservative evangelical leaders get this support precisely because they are part of the daily lives of the faithful”, said Mr. do Valle.

Being such a significant part of the lives of its parishioners — especially the most economically vulnerable — also serves the churches when it comes to politics. “There is an influence, and it is an influence that is greater among evangelicals than among other religious segments,” said Mr. do Valle. “There is a lot of mobilization, a lot of effort from these leaders to make the faithful vote for Bolsonaro.”

In his opinion, the political participation of Brazil’s evangelical community directly reflects what the United States has seen in its own politics.

“There is a very strong exchange between conservative evangelicals in Brazil and conservative evangelicals in the United States,” he said. “This makes Brazil have a type of agenda quite similar to American conservative evangelicals, such as the defense of the state of Israel, or the defense of homeschooling. Themes that dialogue very little with our reality, but even so, they appear in the speech of conservative evangelical leaders in Brazil.”

Political leaders courting the evangelical vote

Politicians in Brazil recognize the power of capturing the evangelical vote. On Wednesday, Lula was forced to issue a public statement reaffirming that he would not abolish evangelical churches if he were elected — a response to a misinformation campaign circulating among churchgoers.

And while the former president and leader of the Workers’ Party has managed to capture 28% of evangelical voting intentions according to Datafolha Institute, his far-right rival has done a much better job in securing a firm grip on the voter base with 68% of evangelicals polled saying they support Bolsonaro.

Ties between Bolsonaro and evangelicals run deep.

The rapprochement between the president and evangelicals became clearer in May 2016 when, as a federal deputy, Bolsonaro was baptized in Israel’s Jordan River by Pastor Everaldo Dias Pereira of the Assembly of God church.

By that time, Bolsonaro and Pastor Everaldo were already old acquaintances. Bolsonaro was a deputy in the Social Christian Party (PSC), which has been chaired by Pastor Everaldo since 2003. (The party currently holds 10 seats in Brazil’s Congress).

His baptism pleased the evangelical public and during the 2018 presidential elections, Bolsonaro received the support of important evangelical leaders such as Pastor Silas Malafaia and Bishop Edir Macedo.

In government, Boslonaro is a staunch defender of key social issues that excite the evangelical base. Condemining abortion under any circumstance, prohibiting sex education in schools and criminalization of drugs are among key rhetorical refrains for the president.

He’s also adopted measures that directly benefit the evangelical elite. In July of this year, the president deregulated the purchase of television time slots for religious propaganda. He also increased tax exemptions for pastors’ salaries and has appointed a number of religious figures to his cabinet and the judiciary, including Supreme Court Justice André Mendonça.

“Pretty much everything that was asked of him, he delivered to evangelicals,” said Mr. do Valle.

His generosity has been met with fidelity by the majority of evangelicals. Leonardo, a white man in his fifties attending the service at Vitória em Cristo Assembly of God church, told Brazil Reports that, “Bolsonaro’s ideas are more compatible with the evangelical public in relation to not being pro-abortion and being pro-family. It’s a matter of aligning ideas. When you choose a representative, you choose a person who has an idea similar to yours, or as close as possible.”

There is a section of evangelicals that doesn’t poll as well for Bolsanaro, however. According to Mr. do Valle, “Among the poorest evangelicals, there is a lower adherence to voting for Jair Bolsonaro, that is, the more people need support from the State, the less they tend to vote for Bolsonaro.” He explains that there exist “cross pressures” of religion and economic conditions that influence this segment of evangelicals.

Mr. do Valle says that for Lula to poll better among evangelicals, he must fight the fake news campaigns that position him as an enemy to the church and understand that evangelicals are a significant section of society whose voices should be listened to.

“It is necessary that the left as a whole and not just Lula understand that evangelicals are an important part of Brazilian society, that it is not possible to think about creating syntheses, a possible union within Brazilian society without taking into account the opinion of evangelicals,” he said.

Differing views about politics within the evangelical church

In my visits to evangelical churches to report this story, it was made clear that there isn’t one cohesive political belief among all members, and temperaments of churchgoers and clergy can range from volatile to welcoming.

On a pleasant, sunny Thursday afternoon, Brazil Reports visited a São Paulo branch of the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, one of the most influential evangelical institutions in the country which owns Brazil’s second largest television station, Record TV. The church’s website encourages followers to fast for 12 hours daily until October 30 in support of Bolsonaro’s reelection.

After service let out, I attempted to begin an interview with a parishioner when from across the hall the pastor wearing a dark suit, white shirt and light tie (who identified himself only as Edson) darted over and interrupted. He ordered his parishioner to leave — she complied. He asked about the nature of my report and when I told him, he said I couldn’t record interviews and began to spew offensive remarks regarding former President Lula.

I asked the pastor if he supported Bolsonaro’s reelection and he replied that his institution was neutral. When asked if Bolsonaro would be the best option for Brazilians this election, he shouted, “Never Lula! Lula never,” called the former president a thief, and repeated the false rumor that Lula plans to close down churches.

I tried to ask a few more questions, but the pastor was reluctant to continue the conversation, despite having calmed down a bit. Instead, I thanked him for his time and left the church.

Not all evangelical pastors, however, agree with the unwavering support for President Bolsonaro, or with the politicization of religious ceremonies in general.

On my visit to the Vitória em Cristo Assembly of God church, I spoke with a pastor who asked to remain anonymous because he was afraid to express his position publicly amid the current political climate.

He said that in more than 56 years of religious life, he has never witnessed so much engagement from evangelical churches in support of one candidate like he’s seeing with Bolsonaro.

For him, churches should stay away from the electoral process, leaving parishioners free to choose who best represents them, without the influence of indoctrination.

“Churches and their leaders must leave evangelical people free to vote for whomever they want,” he told me. “This pro-Bolsonaro political movement of the churches is crossing the line”, said the pastor.