The death of an isolated indigenous man in Brazil’s Amazon, the last of his tribe, weighs heavily on a team of indigenous rights protectors tasked with monitoring him for over a quarter century. It also raises alarms about the need to strengthen policies to protect indigenous people in a country whose government has effectively turned its back on them.

“It’s a very sad scene. Seeing the lifeless body, with a hat on its head, adorned with macaw plumage. The body rested, in its hammock, in its hut, with its objects and belongings. The place he always preferred. [The scene] represents what he was during these almost three decades … Even in his death, he did it his way, alone.”

Those are the words of Altair Algayer, the coordinator for the Guaporé Ethno Environmental Protection Front (FPE Guaporé), a unit of the Brazilian government’s National Indigenous Foundation (Funai) that has worked to protect isolated indigenous peoples since its inception in 1967.

A Funai employee since 1992, Mr. Algayer has monitored the isolated indigenous man, who has come to be known as the “Man of the Hole,” since 1996 when the organization became aware of his existence. For 26 years, Mr. Algayer was the closest person to one of the world’s most isolated individuals.

He spoke exclusively to Brazil Reports about his experience interacting with the Man of the Hole all these years, and what the man’s death means to himself, his team, and to the country.

“We had very close moments, with acceptance of objects, utensils, seeds. [We had] visual contact, we dialogued with him (without ever hearing a single word back),” said Mr. Algayer.

“At great cost, we created a differentiated and respectful relationship. In the first encounters, he even stretched his bow and arrow but never released it at me. I believe he was aware of our good intentions for him, but he always preferred to stay in the forest and in his territory, where he felt most protected.”

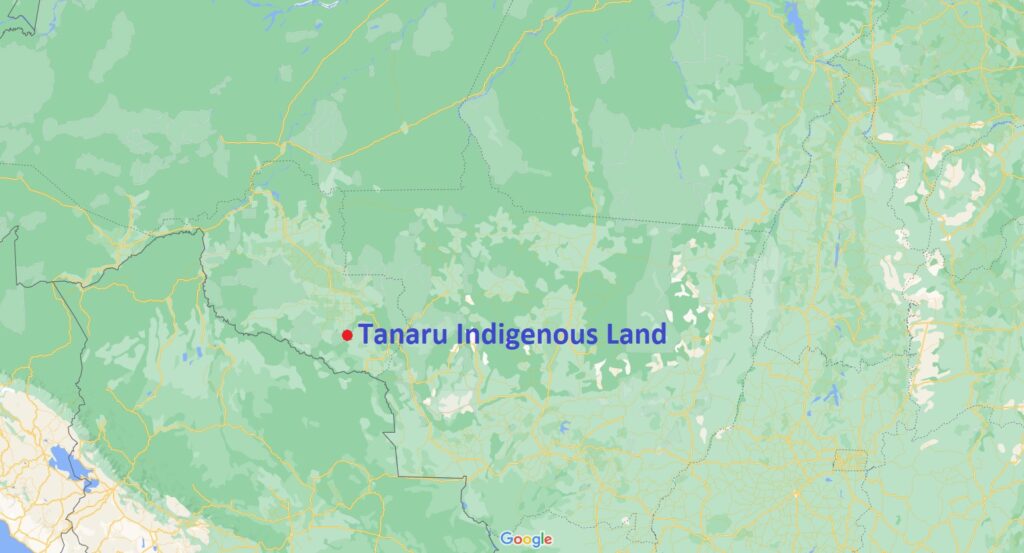

The last known survivor of his ethnicity, the Man of the Hole was found dead on August 23 in his dwelling, located on the Tanaru Indigenous Land in the southern part of the Rondônia state.

In addition to Mr. Algayer, two other people participated in the last monitoring mission during which the man’s body was discovered.

They reported no signs of fighting or violence, nor any traces in the forest indicating the recent presence of humans in the area.

The team thinks that the man had been dead for at least 30 days before being discovered, based on the decomposition of his body, and they estimate his age at death to be somewhere around 60 years old.

The tragic end of a people

The death of the Man of the Hole represents the complete extinction of a people who have never been officially identified by the Brazilian government.

During the 1990s, loggers and ranchers made a series of violent incursions into the Tanaru Indigenous Land, a protected indigenous territory of about 8,000 hectares (19.8 acres) in the Brazilian rainforest which was home to the isolated man’s tribe.

Other members of the tribe were completely killed off during these attacks, and he is believed to be the only survivor, retreating into the forest to live in solitude.

“These people had already been going through successive attacks and escapes in previous times, run over by a policy in favor of economic development and opportunism of many who came to the Amazon in search of exploitation,” said Mr. Algayer. “In this dispute over territory and space, [the Man in the Hole’s tribe] had no chance or possibility to defend themselves. They paid with their lives.”

For years, Brazil had an exclusionary policy towards its indigenous peoples. Between 1964 and 1985, when the country was immersed in a violent military dictatorship, the indigenous peoples of Brazil suffered their longest period of persecution and rights violations.

Launched in July 1970, the National Integration Plan aimed to expand Brazil’s internal borders to generate new business through the creation of new cities, expansion of highways, and facilitating the flow of raw materials. This integration plan resulted in the persecution, criminalization, imprisonment, and torture of indigenous leaders who fought for their territories or who behaved inappropriately according to the standards set by the military.

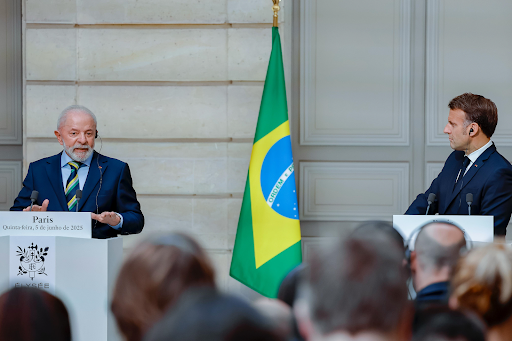

Although there is currently no such aggressive and threatening public policy towards the existence of indigenous peoples, Brazil’s far-right President Jair Bolsonaro has already demonstrated that the protection of these peoples is not one of his priorities.

During his presidency, beginning in 2019, Funai has suffered successive budget cuts, which compromise its performance as a protective unit of the indigenous peoples. (The national directors of Funai did not respond to Brazil Reports’ request for comment. They did release a statement about the indigenous man’s death).

Despite this, Mr. Algayer and his team have gone out on monitoring missions in a helicopter nearly every three months for 26 years to check on the Man of the Hole’s well-being, and they’ve been able to learn a great deal about how he survived in isolation for so long.

Who was the Man of the Hole?

According to Mr. Algayer, the indeginous man’s moniker is derived from his practice of digging a rectangular hole inside his hut 40 centimeters by 80 centimeters and between 1.4 and 1.8 meters deep.

He believes the hole may have some kind of spiritual or religious significance because members of the monitoring team never found any evidence that the hole was used as a place of rest, refuge, or storage, and when the man changed dwellings, he would carefully cover the hole with logs and sticks.

Another member of the Funai monitoring team, who spoke exclusively with Brazil Reports on the condition that they remain anonymous to avoid possible repercussions from the foundation, said that the man looked to be approximately 60 years old, maintained an active lifestyle, and besides being an excellent hunter, was also considered to be very intelligent — clues that help explain how he managed to live alone in the rainforest for so long.

Mr. Algayer also shared details about the Man of the Hole’s eating habits:

“We always found traces of abundant hunting and gathering, using bows and arrows and traps to shoot animals and birds, collecting gongs, fruits, and honey — an activity he mastered very well,” he said.

“At great cost, he accepted some seeds for vegetables such as corn, papaya, cassava, cará, sweet potato, peanuts, and he developed small crops of these.”

From this evidence, Mr. Algayer doesn’t believe that finding food was one of the indigenous man’s biggest problems.

According to the anonymous Funai source, their monitoring expeditions are “periodic depending on the degree of pressure (threats) in the territory.”

“With the Man of the Hole, the monitoring actions were quarterly. Such planning was done to avoid, as much as possible, transiting within the territory occupied by the indigenous man and thus avoiding the spread of disease.”

The urgent need to protect indigenous rights

In the mid-1990s, the Kanindé Ethnoenvironmental Defense Association, an organization that defends indigenous rights, became one of the first entities to locate the Man in the Hole’s isolated tribe in the Tanaru Indigenous Land.

According to Neidinha Suruí, leader of the association, its members found animal traps scattered throughout the region that revealed the existence of isolated peoples in the territory.

“Kanindé was surveying the area of occupation of the indigenous people and in an expedition to the region, it found evidence of such as traps and holes in the ground. We only conducted three expeditions in the region.”

Neidinha says that nowadays, the area where the Man of the Hole lived is surrounded by ranches that use herbicides and pesticides on their plantations, contaminating the water and soil in the region.

For her, the Man of the Hole’s death represents the final extermination of a people and leaves us with the warning that under President Bolsonaro’s government, the rights of these individuals are being constantly threatened.

“The Bolsonaro government, during its administration, has left the lives of isolated and contacted indigenous people in danger with its discourse of not demarcating any more indigenous lands and with a management that has weakened the command and control bodies, in particular Funai, which has gone from being a defender of indigenous rights to a violator of these rights.”

According to the Brazilian Federal Constitution, enacted in 1988, “the lands traditionally occupied by the Indians are intended for their permanent possession, and they are responsible for the exclusive usufruct of the riches of the soil, rivers and lakes therein.”

In 1996, the Brazilian government regulated the demarcation process, the administrative act by which a given territory is identified and signaled as an exclusive property of indigenous peoples. Demarcation is an attribution of the president of the republic and guarantees security for the populations living within these areas, in that it imposes physical limits and access control.

Since taking office in 2019, Jair Bolsonaro has not demarcated any new indigenous lands in Brazil, fulfilling one of his campaign promises when he first ran for office.

Currently, the Brazilian Supreme Court is discussing a thesis that has the potential to cause a severe setback in the struggle of indigenous peoples for recognition of their lands.

The “Temporal Landmark Thesis,” as it is known, is a concept that foresees that only areas occupied by indigenous people up to the date of the promulgation of the Constitution, on October 5, 1988, should be demarcated.

In other words, if the indigenous peoples do not prove that they have inhabited a certain location by October 5, 1988, they will not be able to claim the demarcation of that territory, leaving them vulnerable to invasions by land grabbers, loggers, miners, and ranchers.

To get an idea of what is at stake, Brazil currently has 680 indigenous areas in Funai’s records. Four hundred forty-three have already undergone the demarcation process and are duly regularized by the federal government, and the other 237 are still in some stage of the demarcation process. If the court admits the Temporal Landmark Thesis, indigenous populations from these 237 areas would be obligated to prove in some way that they have been living on that land so that the demarcation can move forward.

Furthermore, in recent years, the Bolsonaro government has “gutted” its environmental protection and forest firefighting agencies, cutting the budgets by 9.8% in 2020 and 27.4% in 2021, according to a report by Observatório do Clima covered in Mongabay. And funding for Funai has all but dried up, according to a United Nations Special Rapporteur who spoke to Greenpeace.

Mr. Algayer, whose Guaporé Ethno Environmental Protection Front functions as a unit of Funai, told Brazil Reports that for a long time now the foundation has been suffering from a process of structural deterioration, with a lack of infrastructure and financial resources, especially in the areas that work directly with indigenous peoples.

He also cites staff shortages at the foundation and a lack of definition of public policy regarding indigenous people as everyday challenges to his work.

The decision of the government to defund organizations like Funai and its rhetoric in support of ranchers and resource extractors entering indigenous lands has led to a “deepening” of violence and rights abuses of indigenous peoples, according to an August report from the Indigenous Missionary Council (CIMI).

Speaking to Brazil Reports at the time, Roberto Liebgott, CIMI regional coordinator, said that the rhetoric from government authorities which is “encouraging the exploitation of indigenous lands by third parties” is leading “the invaders to treat the indigenous people as obstacles to be removed and, in this clash, physical violence becomes the most common path.”

For Ms. Suruí, the rights defender, this type of rhetoric and the very real actions being considered in the Supreme Court are an existential threat to Brazil’s native people’s existence.

“It is urgent that the indigenous lands be demarcated to ensure that other peoples are not extinguished. It is regrettable in the 21st century to see indigenous people disappear. The isolated indigenous person of Tanaru is a symbol of resistance and struggle for all indigenous peoples of the world.”