São Paulo, Brazil — The most polarized election in Brazil’s history was also the most vile on the internet. Reports of xenophobia, religious intolerance and misogyny increased by 39.3% compared to 2021, according to a new study from Safernet, an organization that monitors hate speech online.

Between January 1, 2022 and October 31, 2022, Safernet received 54,888 reports of internet hate crimes compared to 39,379 in the same period last year. This was the third consecutive election (2018, 2020 and 2022) in which there was an increase in complaints. Staggeringly instances of xenophobia, a crime in Brazil, increased by 821%, while religious intolerance grew by 522% and misogyny by 184%.

For Safernet, the numbers indicate that the elections are like a trigger for the advancement of hate speech on the internet, especially on social media. The complaints grow in election years, becoming a powerful political platform to attract the audience’s attention and give visibility and notoriety to criminals.

“Elections have become a fertile field for the growth of hate speech, which feeds on prejudices already rooted in people’s imagination,” said Juliana Cunha, director of Safernet. “The best antidote to hate speech is information and dialogue. As long as we are not able to listen and understand the reality of those who are different, it will be difficult for us to live together respecting differences.”

Xenophobia: prejudice against residents of northeastern

Prejudices between northern and southern Brazil were also evident from the data collected by Safernet.

In the wealthier southern region of Brazil, where there’s a larger population of white, European descendants, and where outgoing President Jair Bolsonaro received a majority of votes, online content that was discriminatory of their northern neighbors was disseminated.

Videos, posts and memes often portrayed Brazil’s northeast — which counts a higher population of indigenous and Afro-Brazilian residents, and where President-elect Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva received a majority of votes — as poor and dependent on the government and the tax money generated by southerners.

There were also posts calling residents of the northeast “dumb” and “manipulated”.

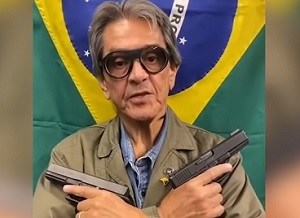

One of the most grievous offenses involved a local trade association vice-president from the southeastern state of Minas Gerais. She posted a video, with two friends and a glass of wine in hand, while badmouthing the north. .

“We generate jobs, pay taxes and spend our money in the northeast,” she said. “We are no longer going to the northeast to give our money to those who live on crumbs. We are going to spend it in the southeast, in the south or even outside the country.”

What does Brazilian law say in these cases?

Xenophobia has been a crime in Brazil since 1997. Being convicted could result in anywhere from a fine to a three-year prison sentence.The crime of xenophobia was included in the Racism Law.

The law prohibits discrimination or prejudice based on race, color, ethnicity, religion or national origin. The punishment also applies to crimes committed on the internet.

As in the United States, hate speech is not a crime in Brazil. However, according to professor and lawyer Cíntia Rosa Pereira de Lima, civil consequences exist for those who practice hate speech, since the Civil Code guarantees the inviolability of intimacy, honor and image.

“The law allows compensation for material and moral damages. And there is also the social damage, which is sometimes a consequence of hate speech, as it can lead a person, for example, to burn down someone’s house,” she said.

“Hate speech can start on the internet and social media and have consequences in the physical world.”