Cara de pau. Literally “wooden face”. This is a Brazilian Portuguese term for, among other things, someone who is shameless. Audacious. Brazen. More topically, it is ideal for charismatic candidates and elected heads of state who run their campaigns on a foundation of populism and controversy.

Of the roughly 80 national and parliamentary elections being held around the world this year, few are as controversial, enthralling and divisive as the general election in Brazil. The run-up to this election has been rife with protests, demonstrations, rallies, the disqualification of former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, and a stabbing of the frontrunner Jair Bolsonaro.

Originally an army parachutist, Bolsonaro served on the Rio de Janeiro city council from 1988 to 1990. This was followed by 26 years in the Brazilian National Congress as a representative of numerous political parties, from the now defunct Christian Democratic Party to the Social Christian Party and Social Liberal Party.

The latter, PSL, nominated Bolsonaro as its candidate for the presidency in July of this year. He was the first candidate this year to raise one million reais, and has remained a strong contender in the polls since before Lula’s disqualification.

Five years ago, this election would have been more remarkable. But following the ascent of Trump in the US, Salvini in Italy, Kurz in Austria, and Duterte in the Philippines, to name just a few, firebrand right-wingers and populists have seemingly become routine.

It is no longer quite so shocking to hear a candidate for Brazil’s presidency say to a former minister, “I said I wouldn’t rape you because you’re not worthy of it.” Gone are the days when it would have been alarming to hear someone of authority waxing romantic about the “glorious” period of “order and progress” enforced by the military government that is credited with the murder and disappearance of hundreds, and the torture of more.

Bolsonaro has also said that Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet “should have killed more” than the 3,000-plus who lost their lives under the regime. In 1999, Bolsonaro stated on television that he would intend to impose a military government on Brazil once more if he were in charge, after dissolving the National Congress of course.

He has been marked as a homophobe, sexist, classist, militant, and an extremist. This, in turn, begs the question that has been plaguing the minds of many in countries who have elected their own populist leaders: why does he enjoy such strong support?

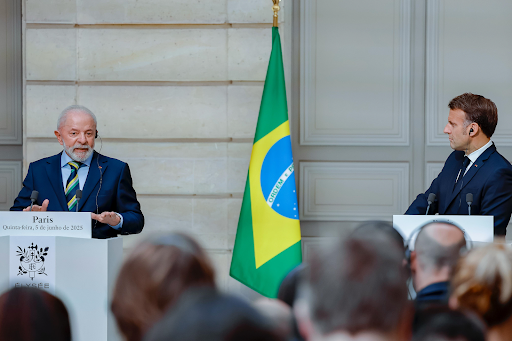

Image courtesy of @MichelTemer – Twitter.

The easy answer is corruption. Incumbent Michel Temer has a 7% approval rating, partly due to charges levied against him for obstruction of justice, bribery, and usage of police violence against critical protesters. Before him came the scandal-ridden Dilma Rousseff, maligned for her involvement in the Petrobras scandal and for causing school shutdowns for millions of students in her refusal to negotiate with professors.

Brazilian newspaper Folha estimates that 30% of all public funds in Brazil are embezzled each year, namely through construction. The Rio Times placed the value of Brazil’s shadow economy at 16.1% of the country’s gross domestic product. Transparency International ranks Brazil at 96 out of 180 in its corruption ranking, but at a mere 37 out of 100 in its score of perceived public sector corruption (0 being “highly corrupt”). To many, Bolsonaro embodies an alternative to years of ineptitude. His salt-of-the-earth manner of speaking is attractive to a voting base that is 14% rural, 65% Catholic and 22% Christian.

Bolsonaro’s views on immigration cannot be ignored. As a virulent opponent of immigrants from the Middle East, Africa, and the Caribbean, his steadfast Brazilians-first attitude is music to the ears of voters who see the international infighting in Europe, Asia, and South America itself as a result of the global refugee crisis. More than 60,000 Venezuelans alone have crossed over into Brazil in recent years, which has placed serious strain on local municipalities.

Another reason for the rise of Bolsonaro, or at least his views, is the game of opposites. The left versus the right. The poor versus the rich, an important metric in a country that Oxfam reports has greater wealth inequality than Uruguay or Argentina and will take 75 years to reach UK levels. It is of no surprise that Bolsonaro’s campaign, like countless others throughout history, seeks to point fingers and hoist the blame onto the “other side.” What is worth analyzing is the sheer volume of these us-versus-them mindsets that has been invoked in Brazil.

These were amplified by the stabbing.

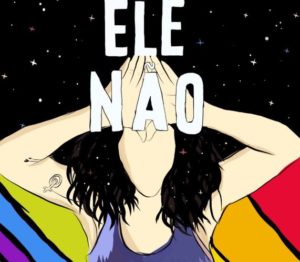

Image courtesy of @KeferaOn – Twitter.

On September 6 Jair Bolsonaro was campaigning in the city of Juiz de Fora, in the state of Minas Gerais. He was stabbed in the stomach by a man who said he was “on a mission from God,” and who has since been arrested. Bolsonaro’s departure from the hospital to return home to Rio de Janeiro was met with protests against his campaign and with the #EleNão (“not him”) movement.

This attack was perceived by Bolsonaro’s supporters as a literal attack on their values. If the left are willing to stab a 63-year-old man simply because of what he says, then they are not fit to run the country. Such is the mindset of those who equate the attacker with the entire left and political mainstream, as opposed to a lone man on a self-imposed mission. Yet it galvanized their resolve, and the hashtag #EleSim (“yes him”) has been making headway.

#EleNão has been tweeted 1,300 times in the last hour at the time of writing, while #EleSim has been tweeted 250 times in that same period. #EleNão has 2,170,000 results on Google, whereas #EleSim has 1,850,000 at the time of writing. Upon being released from the hospital, anti-Bolsonaro protesters rocked all 27 of Brazil’s states. His supporters took to the streets in only 16.

Yet a greater showing of discontent with the controversial figure on social media and in the public arena does not necessarily equate to a lost election. Some polls predicted that Bolsonaro could lose to opponents Geraldo Alckmin, Fernando Haddad, or Ciro Gomes in a run-off later this month. While he received the highest number of votes in the first round on Sunday the 7th, Bolsonaro and Workers’ Party candidate (and Lula’s replacement) Fernando Haddad will face off in a second round on October 28.

Bolsonaro is a shocking man by all accounts. To his critics he is inelegant and brutish at best, and at worst a symptom of all that is wrong with populism and patriarchy. To his supporters he is a breath of fresh air with a blunt honesty and transparency that they are not accustomed to.

In the end, however, he is not surprising. The world is no stranger to this type of rhetoric, nor to the mania that it inspires. As the nation gears up for a second vote in just under three weeks, the future of the world’s 8th-largest economy is wavering on a tightrope.

*The above is an opinion article and does, by no means, represent the editorial viewpoints of Brazil Reports.

Thorin is a translator and freelance reporter from Michigan, currently living in Germany. He chiefly writes about human rights and elections in South America. Follow him on Twitter @EngesethTh.