With Brazil’s presidential elections looming, security is without a doubt one of the most important matters on all candidates’ agendas, as recent spikes in violence have set the nation on edge.

Reducing violence is also within the interests of most urban Brazilian voters, who are tired of petty crime occurring on the streets and living in constant fear. However, the country’s long-standing economic recession has meant that financial allocations to police resources have been lacking for some time.

Speaking to UOL, sociologist and university professor Gabriel Feltran, who is also the author of a recently-published book ‘Brothers – A history of the PCC’ written about South America’s largest criminal organisation, identifies a general misunderstanding in government focus on violence and crime.

Instead of challenging the root cause of the problem, which he implies must be tackled by regulating illegal markets that tend to move these petty crime networks, such as the drugs trade, the government traditionally “focuses on the war against small operators.”

This could perhaps explain why several of this election’s candidates propose a shift to retaliatory security methods such as issuing guns to citizens for self-defence.

Former military officer Jair Bolsonaro, for example, who supports a military intervention into Brazil’s politics and has recently appointed fellow ex-military general Hamilton Mourao as his running mate, proposes that all citizens carry a gun.

Just this week, it was also reported that candidate Geraldo Alckmin also plans to consider slackening arms legislation so that farmers may be allowed to use guns in rural countryside areas.

With the large majority of Brazil’s illegal drugs trade under their command, the PCC (Primeiro Comando Capital) are already South America’s largest criminal organisation. Founded in São Paulo’s Casa da Custódia de Taubaté prison almost 25 years ago, the group have recently come under scrutiny for launching a new expansion policy which uses an ‘adopt-a-brother’ strategy to offer financial incentives as a means of recruiting new members.

Sociologist Feltran also makes the connection between government errors in security policy and the PCC, outlining their misjudgement as one of the three main factors that could encourage growth of the criminal group.

The Washington Post, for example, recently referred to the group’s expansion as a contributing factor in Brazil’s recent crime spikes.

According to investigative journalist and crime researcher with InsightCrime, Mike LaSusa, who spoke to Brazil Reports, the PCC’s expansion can indeed be labelled a “contributing factor” to the country’s increasing levels of violence, but is not the sole cause.

Much of the PCC-related violence stems from conflicts with other Brazilian drug trafficking organisations over territory in the Amazon, he explained, whilst emphasising that economic difficulties, which have resulted in deteriorating healthcare and living conditions, are also behind increased crime rates.

Is it surprising, therefore, that the group’s planned expansion into not only Latin America, but also Europe, is not a pressing issue on this October’s electoral agenda?

The answer, it would seem, is no.

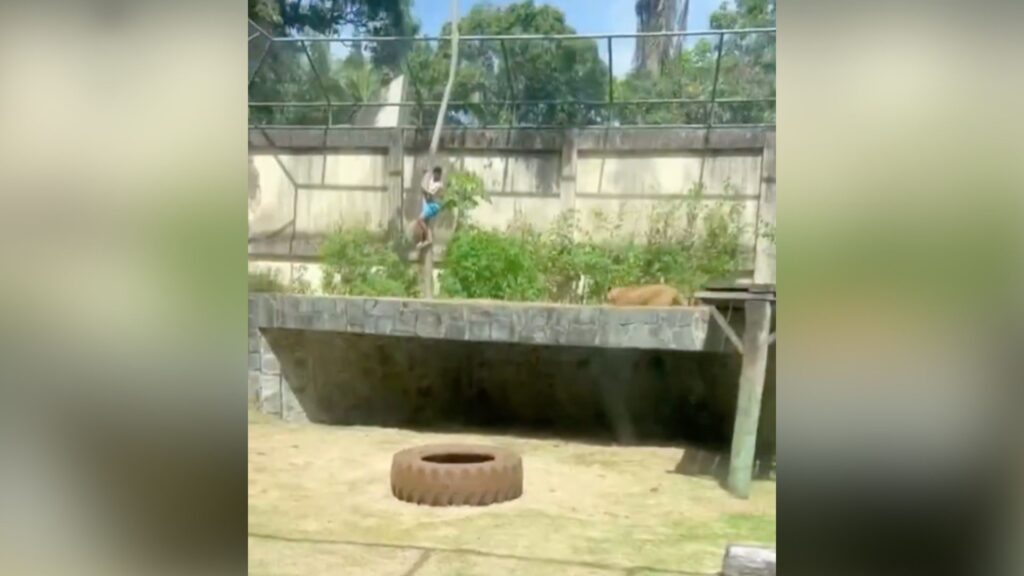

As LaSusa pointed out, the dilemma behind tackling organisations like the PCC is that they are run entirely from prison.

“In my opinion, the PCC is the crime group to watch on the global stage in the coming years,” he pointed out. “I think it will be difficult for them to establish a foothold in Europe and other countries, but if they figure out a way to do it, and even if they don’t, they’re just so massively powerful, violent, well armed and well organised here in Brazil where there’s a massive drug market, that they’re going to be an extremely powerful threat.”

Having been labelled a “brotherhood” and “secret society,” the PCC is unique in the fact that its members are spread throughout Brazil’s prison system. In fact, according to the newspaper Folha de Sao Paulo, members of the PCC constitute approximately 3.5% of Brazil’s inmate population and all of the group’s main leaders are currently imprisoned.

The spread of gang members across all prisons in all of the country’s states can be put down to the paulista government’s 1998 decision to divide forces so that they weren’t all in the same place.

However, in a move intended to halt the PCC’s power, the government actually consolidated the organisation’s strength. As a result, an in-house criminal network was created across Brazil that operates using mobile phones and paying off prison guards.

Given that imprisoning members tends to allow criminal activity to continue from behind bars, the PCC’s expansion is becoming increasingly difficult for police forces to control, which could explain why it does not feature heavily on most candidates’ agendas, advised LaSusa.

Is it a mistake, therefore, for candidates to underestimate the gravity and potential scope of the PCC’s expansion, which could enable them to successfully create their own drug trafficking lines to Europe? Regardless of the answer, it will fall under the responsibilities of Brazil’s next President to deal with the consequences.