Besides the changes he made involving the creation and regulation of Brazil’s indigenous territories, another of Jair Bolsonaro’s first moves in his new role as President was to outline changes in ministerial structure.

Brazil’s new Minister for Women, Family and Human Rights is evangelical pastor Damares Alves, who has an anti-abortion stance.

A self-confessed “terribly Christian” individual, Alves has recently come under fire after a video sharing her controversial opinions on gender ideology was released on the internet last week.

“Attention, attention. It’s a new era in Brazil. Boys wear blue and girls wear pink,” the newly-appointed minister can be seen shouting, proudly and happily, in unison with a crowd of supporters.

Justifying her words as a metaphor for her opinions on gender ideology, Alves refused to apologise to those she has offended with her comments in an interview with GloboNews.

“It was a metaphor,” she said. “We are going to respect children’s biological identity. And, what’s more, we can call girls princesses and boys princes in Brazil, so that there’s no confusion when it comes to this.”

“We don’t want to impose anything,” she continued. “Let’s leave children in peace. You want to discuss this [gender ideology]? Let’s do it in colleges, not in schools, with young children.”

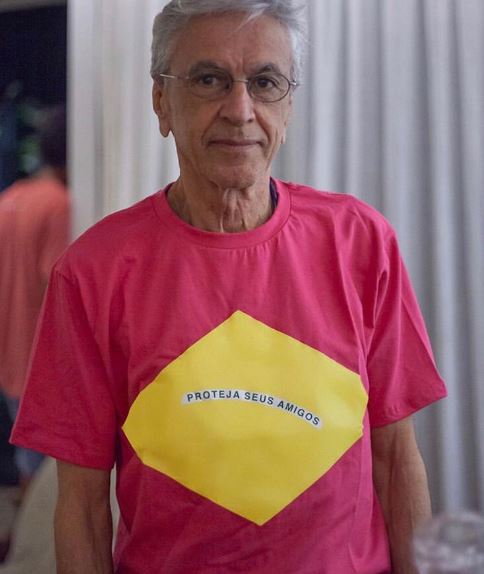

The video has since caused public outcry on social media, where thousands of individuals have protested using the hashtag #GenderHasNoColour. Those who spoke out included world-renowned Brazilian musician Caetano Veloso, who posted a photo of himself wearing a pink t-shirt along with the caption #BoysWearPink.

As part of the structural changes established, a list of minority groups who will be targeted by the ministry for the promotion of human rights was also released. Besides the obvious; women, children, teenagers, youths, the elderly, the disabled, the black population, social and ethnic minorities and indigenous peoples, there was one very obvious minority group missing. Brazil’s LGBT population was not included.

Despite reassurance that the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexuals, transexuals and transvestites will be prioritised by a board rather than a ministry, as has traditionally been the case, Bolsonaro has received criticism for this decision.

For her part, Manuela D’Avila, the Vice President to Bolsonaro’s former campaign opponent Fernando Haddad, shared a negative message last week with her Twitter following.

“In the country that kills the highest number of LGBTs in the world, one of the new president’s first actions is to take the LGBT population out of national human rights directives. Is this governing for all?” she asked, rhetorically.

LGBTphobic violence is indeed rampant in Brazil, a country that saw a 30% increase in the number of deaths registered as relating to sexual orientation from 2016 to 2017, according to The Guardian.

Related: Brazil celebrates signing of National Pact Against LGBTphobic Violence

When it comes to minorities, Bolsonaro’s stance is a topic that has been questioned by his opposition from the start of his presidential campaign. In his first interview as president-elect, he shared his view that Brazil’s minority groups should not be treated any differently to other demographics.

“We’re all the same… It doesn’t matter what the colour of your skin is, your sexual preference, the region where you were born, your gender. We’re all equal … We can’t take certain minorities and think they have superpowers and are different from the others,” he said.

Such comments generated strong reactions from the sister of Marielle Franco, who was assassinated in March 2018 for reasons that are believed to relate to her career as a Rio City Councillor, during which she stood for the rights of Brazil’s most marginalised populations.

Anielle, Franco’s sister, took to speaking out at the Human Rights World Summit against Brazil’s current president’s views.

“Bolsonaro said he is going to ‘clean’ – that’s the way he said it – homosexuals, poor people and black people,” she said. “We are very scared and in danger.”

In fact, Franco is not alone in her fear of Bolsonaro’s stance on minorities. Before his election, members of the LGBT community began a wave of legal action, rushing to complete acts such as marriage and name changes, in fear of losing their rights to do so under a Bolsonaro leadership.

Speaking to The Guardian last year, for example, transgender Pedro Pires shared his angst about losing the right to change his name under a new government. Having put off changing it for financial reasons, he decided to make it a matter of urgency.

Now a week on from his inauguration, Bolsonaro’s decisions as president continue to generate controversy from all angles, particularly on social media. In turn, just as it did during his presidential campaign, his own presence on social media remains an integral part of his governance.